Wikipedia

Human immunodeficiency virus infection / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a disease of the human immune system caused by infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[1] During the initial infection, a person may experience a brief period of influenza-like illness. This is typically followed by a prolonged period without symptoms. As the illness progresses, it interferes more and more with the immune system, making the person much more likely to get infections, including opportunistic infections and tumors that do not usually affect people who have working immune systems.

HIV is transmitted primarily via unprotected sexual intercourse (including anal and even oral sex), contaminated blood transfusions, hypodermic needles, and from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding.[2] Some bodily fluids, such as saliva and tears, do not transmit HIV.[3] Prevention of HIV infection, primarily through safe sex and needle-exchange programs, is a key strategy to control the spread of the disease. There is no cure or vaccine; however, antiretroviral treatment can slow the course of the disease and may lead to a near-normal life expectancy. While antiretroviral treatment reduces the risk of death and complications from the disease, these medications are expensive and may be associated with side effects.

Genetic research indicates that HIV originated in west-central Africa during the early twentieth century.[4] AIDS was first recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1981 and its cause—HIV infection—was identified in the early part of the decade.[5] Since its discovery, AIDS has caused nearly 30 million deaths (as of 2009).[6] As of 2010, approximately 34 million people are living with HIV globally.[7] AIDS is considered a pandemic—a disease outbreak which is present over a large area and is actively spreading.[8]

HIV/AIDS has had a great impact on society, both as an illness and as a source of discrimination. The disease also has significant economic impacts. There are many misconceptions about HIV/AIDS such as the belief that it can be transmitted by casual non-sexual contact. The disease has also become subject to many controversies involving religion.

Signs and symptoms

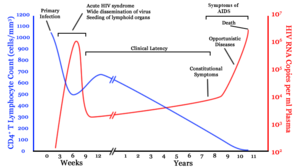

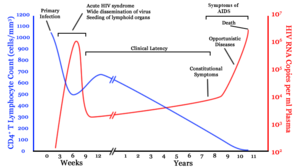

There are three main stages of HIV infection: acute infection, clinical latency and AIDS.[9][10]

Acute infection

Main symptoms of acute HIV infection

The initial period following the contraction of HIV is called acute HIV, primary HIV or acute retroviral syndrome.[9][11] Many individuals develop an influenza-like illness or a mononucleosis-like illness 2–4 weeks post exposure while others have no significant symptoms.[12][13] Symptoms occur in 40–90% of cases and most commonly include fever, large tender lymph nodes, throat inflammation, a rash, headache, and/or sores of the mouth and genitals.[11][13] The rash, which occurs in 20–50% of cases, presents itself on the trunk and is maculopapular, classically.[14] Some people also develop opportunistic infections at this stage.[11] Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting or diarrhea may occur, as may neurological symptoms of peripheral neuropathy or Guillain-Barre syndrome.[13] The duration of the symptoms varies, but is usually one or two weeks.[13]

Due to their nonspecific character, these symptoms are not often recognized as signs of HIV infection. Even cases that do get seen by a family doctor or a hospital are often misdiagnosed as one of the many common infectious diseases with overlapping symptoms. Thus, it is recommended that HIV be considered in patients presenting an unexplained fever who may have risk factors for the infection.[13]

Clinical latency

The initial symptoms are followed by a stage called clinical latency, asymptomatic HIV, or chronic HIV.[10] Without treatment, this second stage of the natural history of HIV infection can last from about three years[15] to over 20 years[16] (on average, about eight years).[17] While typically there are few or no symptoms at first, near the end of this stage many people experience fever, weight loss, gastrointestinal problems and muscle pains.[10] Between 50 and 70% of people also develop persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, characterized by unexplained, non-painful enlargement of more than one group of lymph nodes (other than in the groin) for over three to six months.[9]

Although most HIV-1 infected individuals have a detectable viral load and in the absence of treatment will eventually progress to AIDS, a small proportion (about 5%) retain high levels of CD4+ T cells (T helper cells) without antiretroviral therapy for more than 5 years.[13][18] These individuals are classified as HIV controllers or long-term nonprogressors (LTNP).[18] Another group is those who also maintain a low or undetectable viral load without anti-retroviral treatment who are known as “elite controllers” or “elite suppressors”. They represent approximately 1 in 300 infected persons.[19]

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Main symptoms of AIDS.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is defined in terms of either a CD4+ T cell count below 200 cells per µL or the occurrence of specific diseases in association with an HIV infection.[13] In the absence of specific treatment, around half of people infected with HIV develop AIDS within ten years.[13] The most common initial conditions that alert to the presence of AIDS are pneumocystis pneumonia (40%), cachexia in the form of HIV wasting syndrome (20%) and esophageal candidiasis.[13] Other common signs include recurring respiratory tract infections.[13]

Opportunistic infections may be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites that are normally controlled by the immune system.[20] Which infections occur partly depends on what organisms are common in the person’s environment.[13] These infections may affect nearly every organ system.[21]

People with AIDS have an increased risk of developing various viral induced cancers including: Kaposi’s sarcoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and cervical cancer.[14] Kaposi’s sarcoma is the most common cancer occurring in 10 to 20% of people with HIV.[22] The second most common cancer is lymphoma which is the cause of death of nearly 16% of people with AIDS and is the initial sign of AIDS in 3 to 4%.[22] Both these cancers are associated with human herpesvirus 8.[22] Cervical cancer occurs more frequently in those with AIDS due to its association with human papillomavirus (HPV).[22]

Additionally, people with AIDS frequently have systemic symptoms such as prolonged fevers, sweats (particularly at night), swollen lymph nodes, chills, weakness, and weight loss.[23] Diarrhea is another common symptom present in about 90% of people with AIDS.[24]

Transmission

Average per act risk of getting HIV

by exposure route to an infected source

| Exposure Route |

Chance of infection |

| Blood Transfusion |

90% [25] |

| Childbirth (to child) |

25%[26] |

| Needle-sharing injection drug use |

0.67%[25] |

| Percutaneous needle stick |

0.30%[27] |

| Receptive anal intercourse* |

0.04–3.0%[28] |

| Insertive anal intercourse* |

0.03%[29] |

| Receptive penile-vaginal intercourse* |

0.05–0.30%[28][30] |

| Insertive penile-vaginal intercourse* |

0.01–0.38% [28][30] |

| Receptive oral intercourse*§ |

0–0.04% [28] |

| Insertive oral intercourse*§ |

0–0.005%[31] |

* assuming no condom use

§ source refers to oral intercourse

performed on a man |

HIV is transmitted by three main routes: sexual contact, exposure to infected body fluids or tissues, and from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding (known as vertical transmission).[2] There is no risk of acquiring HIV if exposed to feces, nasal secretions, saliva, sputum, sweat, tears, urine, or vomit unless these are contaminated with blood.[27] It is possible to be co-infected by more than one strain of HIV—a condition known as HIV superinfection.[32]

Sexual

The most frequent mode of transmission of HIV is through sexual contact with an infected person.[2] The majority of all transmissions occur through heterosexual contacts (i.e. sexual contacts between people of the opposite sex);[2] however, the pattern of transmission varies significantly among countries. In the United States, as of 2009, most sexual transmission occurred in men who had sex with men,[2] with this population accounting for 64% of all new cases.[33]

As regards unprotected heterosexual contacts, estimates of the risk of HIV transmission per sexual act appear to be four to ten times higher in low-income countries than in high-income countries.[34] In low-income countries, the risk of female-to-male transmission is estimated as 0.38% per act, and of male-to-female transmission as 0.30% per act; the equivalent estimates for high-income countries are 0.04% per act for female-to-male transmission, and 0.08% per act for male-to-female transmission.[34] The risk of transmission from anal intercourse is especially high, estimated as 1.4–1.7% per act in both heterosexual and homosexual contacts.[34][35] While the risk of transmission from oral sex is relatively low, it is still present.[36] The risk from receiving oral sex has been described as “nearly nil”[37] however a few cases have been reported.[38] The per-act risk is estimated at 0–0.04% for receptive oral intercourse.[39] In settings involving prostitution in low income countries, risk of female-to-male transmission has been estimated as 2.4% per act and male-to-female transmission as 0.05% per act.[34]

Risk of transmission increases in the presence of many sexually transmitted infections[40] and genital ulcers.[34] Genital ulcers appear to increase the risk approximately fivefold.[34] Other sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and bacterial vaginosis, are associated with somewhat smaller increases in risk of transmission.[39]

The viral load of an infected person is an important risk factor in both sexual and mother-to-child transmission.[41] During the first 2.5 months of an HIV infection a person’s infectiousness is twelve times higher due to this high viral load.[39] If the person is in the late stages of infection, rates of transmission are approximately eightfold greater.[34]

Rough sex can be a factor associated with an increased risk of transmission.[42] Sexual assault is also believed to carry an increased risk of HIV transmission as condoms are rarely worn, physical trauma to the vagina or rectum is likely, and there may be a greater risk of concurrent sexually transmitted infections.[43]

Body fluids

CDC poster from 1989 highlighting the threat of AIDS associated with drug use

The second most frequent mode of HIV transmission is via blood and blood products.[2] Blood-borne transmission can be through needle-sharing during intravenous drug use, needle stick injury, transfusion of contaminated blood or blood product, or medical injections with unsterilised equipment. The risk from sharing a needle during drug injection is between 0.63 and 2.4% per act, with an average of 0.8%.[44] The risk of acquiring HIV from a needle stick from an HIV-infected person is estimated as 0.3% (about 1 in 333) per act and the risk following mucus membrane exposure to infected blood as 0.09% (about 1 in 1000) per act.[27] In the United States intravenous drug users made up 12% of all new cases of HIV in 2009,[33] and in some areas more than 80% of people who inject drugs are HIV positive.[2]

HIV is transmitted in About 93% of blood transfusions involving infected blood .[44] In developed countries the risk of acquiring HIV from a blood transfusion is extremely low (less than one in half a million) where improved donor selection and HIV screening is performed;[2] for example, in the UK the risk is reported at one in five million.[45] In low income countries, only half of transfusions may be appropriately screened (as of 2008),[46] and it is estimated that up to 15% of HIV infections in these areas come from transfusion of infected blood and blood products, representing between 5% and 10% of global infections.[2][47]

Unsafe medical injections play a significant role in HIV spread in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2007, between 12 and 17% of infections in this region were attributed to medical syringe use.[48] The World Health Organisation estimates the risk of transmission as a result of a medical injection in Africa at 1.2%.[48] Significant risks are also associated with invasive procedures, assisted delivery, and dental care in this area of the world.[48]

People giving or receiving tattoos, piercings, and scarification are theoretically at risk of infection but no confirmed cases have been documented.[49] It is not possible for mosquitoes or other insects to transmit HIV.[50]

Mother-to-child

HIV can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, during delivery, or through breast milk.[51][52] This is the third most common way in which HIV is transmitted globally.[2] In the absence of treatment, the risk of transmission before or during birth is around 20% and in those who also breastfeed 35%.[51] As of 2008, vertical transmission accounted for about 90% of cases of HIV in children.[51] With appropriate treatment the risk of mother-to-child infection can be reduced to about 1%.[51] Preventive treatment involves the mother taking antiretroviral during pregnancy and delivery, an elective caesarean section, avoiding breastfeeding, and administering antiretroviral drugs to the newborn.[53] Many of these measures are however not available in the developing world.[53] If blood contaminates food during pre-chewing it may pose a risk of transmission.[49]

Virology

A diagram showing the structure of HIV virus

HIV is the cause of the spectrum of disease known as HIV/AIDS. HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects components of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. It directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells.[54]

HIV is a member of the genus Lentivirus,[55] part of the family of Retroviridae.[56] Lentiviruses share many morphological and biological characteristics. Many species of mammals are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses with a long incubation period.[57] Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon entry into the target cell, the viral RNA genome is converted (reverse transcribed) into double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase that is transported along with the viral genome in the virus particle. The resulting viral DNA is then imported into the cell nucleus and integrated into the cellular DNA by a virally encoded integrase and host co-factors.[58] Once integrated, the virus may become latent, allowing the virus and its host cell to avoid detection by the immune system.[59] Alternatively, the virus may be transcribed, producing new RNA genomes and viral proteins that are packaged and released from the cell as new virus particles that begin the replication cycle anew.[60]

Two types of HIV have been characterized: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that was originally discovered (and initially referred to also as LAV or HTLV-III). It is more virulent, more infective,[61] and is the cause of the majority of HIV infections globally. The lower infectivity of HIV-2 as compared with HIV-1 implies that fewer people exposed to HIV-2 will be infected per exposure. Because of its relatively poor capacity for transmission, HIV-2 is largely confined to West Africa.[62]

Pathophysiology

After the virus enters the body there is a period of rapid viral replication, leading to an abundance of virus in the peripheral blood. During primary infection, the level of HIV may reach several million virus particles per milliliter of blood.[63] This response is accompanied by a marked drop in the number of circulating CD4+ T cells. The acute viremia is almost invariably associated with activation of CD8+ T cells, which kill HIV-infected cells, and subsequently with antibody production, or seroconversion. The CD8+ T cell response is thought to be important in controlling virus levels, which peak and then decline, as the CD4+ T cell counts recover. A good CD8+ T cell response has been linked to slower disease progression and a better prognosis, though it does not eliminate the virus.[64]

The pathophysiology of AIDS is complex.[65] Ultimately, HIV causes AIDS by depleting CD4+ T cells. This weakens the immune system and allows opportunistic infections. T cells are essential to the immune response and without them, the body cannot fight infections or kill cancerous cells. The mechanism of CD4+ T cell depletion differs in the acute and chronic phases.[66] During the acute phase, HIV-induced cell lysis and killing of infected cells by cytotoxic T cells accounts for CD4+ T cell depletion, although apoptosis may also be a factor. During the chronic phase, the consequences of generalized immune activation coupled with the gradual loss of the ability of the immune system to generate new T cells appear to account for the slow decline in CD4+ T cell numbers.[67]

Although the symptoms of immune deficiency characteristic of AIDS do not appear for years after a person is infected, the bulk of CD4+ T cell loss occurs during the first weeks of infection, especially in the intestinal mucosa, which harbors the majority of the lymphocytes found in the body.[68] The reason for the preferential loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells is that the majority of mucosal CD4+ T cells express the CCR5 protein which HIV uses as a co-receptor to gain access to the cells, whereas only a small fraction of CD4+ T cells in the bloodstream do so.[69]

HIV seeks out and destroys CCR5 expressing CD4+ T cells during acute infection.[70] A vigorous immune response eventually controls the infection and initiates the clinically latent phase. CD4+ T cells in mucosal tissues remain particularly affected.[70] Continuous HIV replication causes a state of generalized immune activation persisting throughout the chronic phase.[71] Immune activation, which is reflected by the increased activation state of immune cells and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, results from the activity of several HIV gene products and the immune response to ongoing HIV replication. It is also linked to the breakdown of the immune surveillance system of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier caused by the depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells during the acute phase of disease.[72]

Diagnosis

A generalized graph of the relationship between HIV copies (viral load) and CD4+ T cell counts over the average course of untreated HIV infection. CD4+ T Lymphocyte count (cells/mm³) HIV RNA copies per mL of plasma

HIV/AIDS is diagnosed via laboratory testing and then staged based on the presence of certain signs or symptoms.[11] HIV testing is recommended for all those at high risk, which includes anyone diagnosed with a sexually transmitted illness.[14] In many areas of the world a third of HIV carriers only discover they are infected at an advanced stage of the disease when AIDS or severe immunodeficiency has become apparent.[14]

HIV testing

Most people infected with HIV develop specific antibodies (i.e. seroconvert) within three to twelve weeks of the initial infection.[13] Diagnosis of primary HIV before seroconversion is done by measuring HIV-RNA or p24 antigen.[13] Positive results obtained by antibody or PCR testing are confirmed either by a different antibody or by PCR.[11]

Antibody tests in children younger than 18 months are typically inaccurate due to the continued presence of maternal antibodies.[73] Thus HIV infection can only be diagnosed by PCR testing for HIV RNA or DNA, or via testing for the p24 antigen.[11] Much of the world lacks access to reliable PCR testing and many places simply wait until either symptoms develop or the child is old enough for accurate antibody testing.[73] In sub-Saharan Africa as of 2007–2009 between 30 and 70% of the population was aware of their HIV status.[74] In 2009, between 3.6 and 42% of men and women in Sub-Saharan countries were tested[74] which represented a significant increase compared to previous years.[74]

Classifications of HIV infection

Two main clinical staging systems are used to classify HIV and HIV-related disease for surveillance purposes: the WHO disease staging system for HIV infection and disease,[11] and the CDC classification system for HIV infection.[75] The CDC‘s classification system is more frequently adopted in developed countries. Since the WHO‘s staging system does not require laboratory tests, it is suited to the resource-restricted conditions encountered in developing countries, where it can also be used to help guide clinical management. Despite their differences, the two systems allow comparison for statistical purposes.[9][11][75]

The World Health Organization first proposed a definition for AIDS in 1986.[11] Since then, the WHO classification has been updated and expanded several times, with the most recent version being published in 2007.[11] The WHO system uses the following categories:

The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention also created a classification system for HIV, and updated it in 2008.[75] This system classifies HIV infections based on CD4 count and clinical symptoms,[75] and describes the infection in three stages:

- Stage 1: CD4 count ≥ 500 cells/µl and no AIDS defining conditions

- Stage 2: CD4 count 200 to 500 cells/µl and no AIDS defining conditions

- Stage 3: CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/µl or AIDS defining conditions

- Unknown: if insufficient information is available to make any of the above classifications

For surveillance purposes, the AIDS diagnosis still stands even if, after treatment, the CD4+ T cell count rises to above 200 per µL of blood or other AIDS-defining illnesses are cured.[9]

Prevention

AIDS Clinic,

McLeod Ganj, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2010

Sexual contact

Consistent condom use reduces the risk of HIV transmission by approximately 80% over the long term.[76] When condoms are used consistently by a couple in which one person is infected, the rate of HIV infection is less than 1% per year.[77] There is some evidence to suggest that female condoms may provide an equivalent level of protection.[78] Application of a vaginal gel containing tenofovir (a reverse transcriptase inhibitor) immediately before sex seems to reduce infection rates by approximately 40% among African women.[79] By contrast, use of the spermicide nonoxynol-9 may increase the risk of transmission due to its tendency to cause vaginal and rectal irritation.[80] Circumcision in Sub-Saharan Africa “reduces the acquisition of HIV by heterosexual men by between 38% and 66% over 24 months”.[81] Based on these studies, the World Health Organization and UNAIDS both recommended male circumcision as a method of preventing female-to-male HIV transmission in 2007.[82] Whether it protects against male-to-female transmission is disputed[83][84] and whether it is of benefit in developed countries and among men who have sex with men is undetermined.[85][86][87] Some experts fear that a lower perception of vulnerability among circumcised men may cause more sexual risk-taking behavior, thus negating its preventive effects.[88]

Programs encouraging sexual abstinence do not appear to affect subsequent HIV risk.[89] Evidence for a benefit from peer education is equally poor.[90] Comprehensive sexual education provided at school may decrease high risk behavior.[91] A substantial minority of young people continues to engage in high-risk practices despite knowing about HIV/AIDS, underestimating their own risk of becoming infected with HIV.[92] It is not known whether treating other sexually transmitted infections is effective in preventing HIV.[40]

Pre-exposure

Treating people with HIV whose CD4 count ≥ 350cells/µL with antiretrovirals protects 96% of their partners from infection.[93] This is about a 10 to 20 fold reduction in transmission risk.[94] Pre-exposure prophylaxis with a daily dose of the medications tenofovir, with or without emtricitabine, is effective in a number of groups including men who have sex with men, couples where one is HIV positive, and young heterosexuals in Africa.[79]

Universal precautions within the health care environment are believed to be effective in decreasing the risk of HIV.[95] Intravenous drug use is an important risk factor and harm reduction strategies such as needle-exchange programmes and opioid substitution therapy appear effective in decreasing this risk.[96][97]

Post-exposure

A course of antiretrovirals administered within 48 to 72 hours after exposure to HIV positive blood or genital secretions is referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis.[98] The use of the single agent zidovudine reduces the risk of subsequent HIV infection fivefold following a needle stick injury.[98] Treatment is recommended after sexual assault when the perpetrator is known to be HIV positive but is controversial when their HIV status is unknown.[99] Current treatment regimes typically use lopinavir/ritonavir and lamivudine/zidovudine or emtricitabine/tenofovir and may decrease the risk further.[98] The duration of treatment is usually four weeks[100] and is frequently associated with adverse effects (with zidovudine in about 70% of cases, including nausea in 24%, fatigue in 22%, emotional distress in 13%, and headaches in 9%).[27]

Mother-to-child

Programs to prevent the vertical transmission of HIV (from mothers to children) can reduce rates of transmission by 92–99%.[51][96] This primarily involves the use of a combination of antiviral medications during pregnancy and after birth in the infant and potentially includes bottle feeding rather than breastfeeding.[51][101] If replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable, and safe, mothers should avoid breastfeeding their infants; however exclusive breastfeeding is recommended during the first months of life if this is not the case.[102] If exclusive breastfeeding is carried out, the provision of extended antiretroviral prophylaxis to the infant decreases the risk of transmission.[103]

Vaccination

As of 2012 there is no effective vaccine for HIV or AIDS.[104] A single trial of the vaccine RV 144 published in 2009 found a partial reduction in the risk of transmission of roughly 30%, stimulating some hope in the research community of developing a truly effective vaccine.[105] Further trials of the RV 144 vaccine are ongoing.[106][107]

Management

There is currently no cure or effective HIV vaccine. Treatment consists of high active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) which slows progression of the disease[108] and as of 2010 more than 6.6 million people were taking them in low and middle income countries.[7] Treatment also includes preventive and active treatment of opportunistic infections.

Antiviral therapy

Abacavir – a nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NARTI or NRTI)

Current HAART options are combinations (or “cocktails”) consisting of at least three medications belonging to at least two types, or “classes,” of antiretroviral agents.[109] Initially treatment is typically a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) plus two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs).[109] Typical NRTIs include: zidovudine (AZT) or tenofovir (TDF) and lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC).[109] Combinations of agents which include a protease inhibitors (PI) are used if the above regime loses effectiveness.[109]

When to start antiretroviral therapy is subject to debate.[14][110] The World Health Organization, European guidelines and the United States recommends antiretrovirals in all adolescents, adults and pregnant women with a CD4 count less than 350/uL or those with symptoms regardless of CD4 count.[14][109] This is supported by the fact that beginning treatment at this level reduces the risk of death.[111] The United States in addition recommends them for all HIV-infected people regardless of CD4 count or symptoms; however it makes this recommendation with less confidence for those with higher counts.[112] While the WHO also recommends treatment in those who are co-infected with tuberculosis and those with chronic active hepatitis B.[109] Once treatment is begun it is recommended that it is continued without breaks or “holidays”.[14] Many people are diagnosed only after treatment ideally should have begun.[14] The desired outcome of treatment is a long term plasma HIV-RNA count below 50 copies/mL.[14] Levels to determine if treatment is effective are initially recommended after four weeks and once levels fall below 50 copies/mL checks every three to six months are typically adequate.[14] Inadequate control is deemed to be greater than 400 copies/mL.[14] Based on these criteria treatment is effective in more than 95% of people during the first year.[14]

Benefits of treatment include a decreased risk of progression to AIDS and a decreased risk of death.[113] In the developing world treatment also improves physical and mental health.[114] With treatment there is a 70% reduced risk of acquiring tuberculosis.[109] Additional benefits include a decreased risk of transmission of the disease to sexual partners and a decrease in mother-to-child transmission.[109] The effectiveness of treatment depends to a large part on compliance.[14] Reasons for non-adherence include poor access to medical care,[115] inadequate social supports, mental illness and drug abuse.[116] The complexity of treatment regimens (due to pill numbers and dosing frequency) and adverse effects may reduce adherence.[117] Even though cost is an important issue with some medications,[118] 47% of those who needed them were taking them in low and middle income countries as of 2010[7] and the rate of adherence is similar in low-income and high-income countries.[119]

Specific adverse events are related to the agent taken.[120] Some relatively common ones include: lipodystrophy syndrome, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus especially with protease inhibitors.[9] Other common symptoms include diarrhea,[120][121] and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[122] Newer recommended treatments are associated with fewer adverse effects.[14] Certain medications may be associated with birth defects and therefore may be unsuitable for women hoping to have children.[14]

Treatment recommendations for children are slightly different from those for adults. In the developing world, as of 2010, 23% of children who were in need of treatment had access.[123] Both the World Health Organization and the United States recommend treatment for all children less than twelve months of age.[124][125] The United States recommends in those between one year and five years of age treatment in those with HIV RNA counts of greater than 100,000 copies/mL, and in those more than five years treatments when CD4 counts are less than 500/ul.[124]

Opportunistic infections

Measures to prevent opportunistic infections are effective in many people with HIV/AIDS. In addition to improving current disease, treatment with antiretrovirals reduces the risk of developing additional opportunistic infections.[120] Vaccination against hepatitis A and B is advised for all people at risk of HIV before they become infected; however it may also be given after infection.[126] Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis between four and six weeks of age and ceasing breastfeeding in infants born to HIV positive mothers is recommended in resource limited settings.[123] It is also recommended to prevent PCP when a person’s CD4 count is below 200 cells/uL and in those who have or have previously had PCP.[127] People with substantial immunosuppression are also advised to receive prophylactic therapy for toxoplasmosis and Cryptococcus meningitis.[128] Appropriate preventive measures have reduced the rate of these infections by 50% between 1992 and 1997.[129]

Alternative medicine

In the US, approximately 60% of people with HIV use various forms of complementary or alternative medicine,[130] even though the effectiveness of most of these therapies has not been established.[131] With respect to dietary advice and AIDS some evidence has shown a benefit from micronutrient supplements.[132] Evidence for supplementation with selenium is mixed with some tentative evidence of benefit.[133] There is some evidence that vitamin A supplementation in children reduces mortality and improves growth.[132] In Africa in nutritionally compromised pregnant and lactating women a multivitamin supplementation has improved outcomes for both mothers and children.[132] Dietary intake of micronutrients at RDA levels by HIV-infected adults is recommended by the World Health Organization.[134][135] The WHO further states that several studies indicate that supplementation of vitamin A, zinc, and iron can produce adverse effects in HIV positive adults.[135] There is not enough evidence to support the use of herbal medicines.[136]

Prognosis

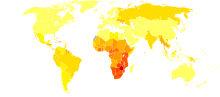

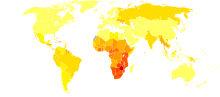

Disability-adjusted life yearfor HIV and AIDS per 100,000 inhabitants as of 2004.

no data

≤ 10

10–25

25–50

50–100

100–500

500–1000

|

1000–2500

2500–5000

5000–7500

7500-10000

10000-50000

≥ 50000

|

HIV/AIDS has become a chronic rather than an acutely fatal disease in many areas of the world.[137] Prognosis varies between people, and both the CD4 count and viral load are useful for predicted outcomes.[13] Without treatment, average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.[138] After the diagnosis of AIDS, if treatment is not available, survival ranges between 6 and 19 months.[139][140] HAART and appropriate prevention of opportunistic infections reduces the death rate by 80%, and raises the life expectancy for a newly diagnosed young adult to 20–50 years.[137][141][142] This is between two thirds[141] and nearly that of the general population.[14][143] If treatment is started late in the infection, prognosis is not as good:[14] for example, if treatment is begun following the diagnosis of AIDS, life expectancy is ~10–40 years.[14][137] Half of infants born with HIV die before two years of age without treatment.[123]

The primary causes of death from HIV/AIDS are opportunistic infections and cancer, both of which are frequently the result of the progressive failure of the immune system.[129][144] Risk of cancer appears to increase once the CD4 count is below 500/μL.[14] The rate of clinical disease progression varies widely between individuals and has been shown to be affected by a number of factors such as a person’s susceptibility and immune function;[145] their access to health care, the presence of co-infections;[139][146] and the particular strain (or strains) of the virus involved.[147][148]

Tuberculosis co-infection is one of the leading causes of sickness and death in those with HIV/AIDS being present in a third of all HIV infected people and causing 25% of HIV related deaths.[149] HIV is also one of the most important risk factors for tuberculosis.[150] Hepatitis C is another very common co-infection where each disease increases the progression of the other.[151] The two most common cancers associated with HIV/AIDS are Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.[144]

Even with anti-retroviral treatment, over the long term HIV-infected people may experience neurocognitive disorders,[152] osteoporosis,[153] neuropathy,[154] cancers,[155][156] nephropathy,[157] and cardiovascular disease.[121] It is not clear whether these conditions result from the HIV infection itself or are adverse effects of treatment.

Epidemiology

Estimated

prevalence of HIV among young adults (15–49) per country as of 2011.

[158]

HIV/AIDS is a global pandemic.[159] As of 2010, approximately 34 million people have HIV worldwide.[7] Of these approximately 16.8 million are women and 3.4 million are less than 15 years old.[7] It resulted in about 1.8 million deaths in 2010, down from a peak of 2.2 million in 2005.[7]

Sub-Saharan Africa is the region most affected. In 2010, an estimated 68% (22.9 million) of all HIV cases and 66% of all deaths (1.2 million) occurred in this region.[160] This means that about 5% of the adult population is infected[161] and it is believed to be the cause of 10% of all deaths in children.[162] Here in contrast to other regions women compose nearly 60% of cases.[160] South Africa has the largest population of people with HIV of any country in the world at 5.9 million.[160] Life expectancy has fallen in the worst-affected countries due to HIV/AIDS; for example, in 2006 it was estimated that it had dropped from 65 to 35 years in Botswana.[8]

South & South East Asia is the second most affected; in 2010 this region contained an estimated 4 million cases or 12% of all people living with HIV resulting in approximately 250,000 deaths.[161] Approximately 2.4 million of these cases are in India.[160]

In 2008 in the United States approximately 1.2 million people were living with HIV, resulting in about 17,500 deaths. The Centre for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in 2008 20% of infected Americans were unaware of their infection.[163] In the United Kingdom as of 2009 there where approximately 86,500 cases which resulted in 516 deaths.[164] In Canada as of 2008 there were about 65,000 cases causing 53 deaths.[165] Between the first recognition of AIDS in 1981 and 2009 it has led to nearly 30 million deaths.[6] Prevalence is lowest in Middle East and North Africa at 0.1% or less, East Asia at 0.1% and Western and Central Europe at 0.2%.[161]

History

Discovery

AIDS was first clinically observed in 1981 in the United States.[22] The initial cases were a cluster of injecting drug users and homosexual men with no known cause of impaired immunity who showed symptoms of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), a rare opportunistic infection that was known to occur in people with very compromised immune systems.[166] Soon thereafter, an unexpected number of gay men developed a previously rare skin cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS).[167][168] Many more cases of PCP and KS emerged, alerting U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and a CDC task force was formed to monitor the outbreak.[169]

Robert Gallo, co-discoverer of HIV in the early eighties among (from left to right) Sandra Eva, Sandra Colombini, and Ersell Richardson.

In the early days, the CDC did not have an official name for the disease, often referring to it by way of the diseases that were associated with it, for example, lymphadenopathy, the disease after which the discoverers of HIV originally named the virus.[170][171] They also used Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections, the name by which a task force had been set up in 1981.[172] At one point, the CDC coined the phrase “the 4H disease”, since the syndrome seemed to affect Haitians, homosexuals, hemophiliacs, and heroin users.[173] In the general press, the term “GRID”, which stood for gay-related immune deficiency, had been coined.[174] However, after determining that AIDS was not isolated to the gay community,[172] it was realized that the term GRID was misleading and the term AIDS was introduced at a meeting in July 1982.[175] By September 1982 the CDC started referring to the disease as AIDS.[176]

In 1983, two separate research groups led by Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier independently declared that a novel retrovirus may have been infecting AIDS patients, and published their findings in the same issue of the journal Science.[177][178] Gallo claimed that a virus his group had isolated from an AIDS patient was strikingly similar in shape to other human T-lymphotropic viruses (HTLVs) his group had been the first to isolate. Gallo’s group called their newly isolated virus HTLV-III. At the same time, Montagnier’s group isolated a virus from a patient presenting with swelling of the lymph nodes of the neck and physical weakness, two characteristic symptoms of AIDS. Contradicting the report from Gallo’s group, Montagnier and his colleagues showed that core proteins of this virus were immunologically different from those of HTLV-I. Montagnier’s group named their isolated virus lymphadenopathy-associated virus (LAV).[169] As these two viruses turned out to be the same, in 1986, LAV and HTLV-III were renamed HIV.[179]

Origins

Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 are believed to have originated in non-human primates in West-central Africa and were transferred to humans in the early 20th century.[4] HIV-1 appears to have originated in southern Cameroon through the evolution of SIV(cpz), a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) that infects wild chimpanzees (HIV-1 descends from the SIVcpz endemic in the chimpanzee subspecies Pan troglodytes troglodytes).[180][181] The closest relative of HIV-2 is SIV(smm), a virus of the sooty mangabey (Cercocebus atys atys), an Old World monkey living in coastal West Africa (from southern Senegal to western Côte d’Ivoire).[62] New World monkeys such as the owl monkey are resistant to HIV-1 infection, possibly because of a genomic fusion of two viral resistance genes.[182] HIV-1 is thought to have jumped the species barrier on at least three separate occasions, giving rise to the three groups of the virus, M, N, and O.[183]

There is evidence that humans who participate in bushmeat activities, either as hunters or as bushmeat vendors, commonly acquire SIV.[184] However, SIV is a weak virus which is typically suppressed by the human immune system within weeks of infection. It is thought that several transmissions of the virus from individual to individual in quick succession are necessary to allow it enough time to mutate into HIV.[185] Furthermore, due to its relatively low person-to-person transmission rate, SIV can only spread throughout the population in the presence of one or more high-risk transmission channels, which are thought to have been absent in Africa before the 20th century.

Specific proposed high-risk transmission channels, allowing the virus to adapt to humans and spread throughout the society, depend on the proposed timing of the animal-to-human crossing. Genetic studies of the virus suggest that the most recent common ancestor of the HIV-1 M group dates back to circa 1910.[186] Proponents of this dating link the HIV epidemic with the emergence of colonialism and growth of large colonial African cities, leading to social changes, including a higher degree of sexual promiscuity, the spread of prostitution, and the accompanying high frequency of genital ulcer diseases (such as syphilis) in nascent colonial cities.[187] While transmission rates of HIV during vaginal intercourse are low under regular circumstances, they are increased many fold if one of the partners suffers from a sexually transmitted infection causing genital ulcers. Early 1900s colonial cities were notable due to their high prevalence of prostitution and genital ulcers, to the degree that, as of 1928, as many as 45% of female residents of eastern Kinshasa were thought to have been prostitutes, and, as of 1933, around 15% of all residents of the same city had syphilis.[187]

An alternative view holds that unsafe medical practices in Africa after World War II, such as unsterile reuse of single use syringes during mass vaccination, antibiotic and anti-malaria treatment campaigns, were the initial vector that allowed the virus to adapt to humans and spread.[185][188][189]

The earliest well documented case of HIV in a human dates back to 1959 in the Congo.[190] The virus may have been present in the United States as early as 1966,[191] but the vast majority of infections occurring outside sub-Saharan Africa (including the U.S.) can be traced back to a single unknown individual who became infected with HIV in Haiti and then brought the infection to the United States some time around 1969.[192] The epidemic then rapidly spread among high-risk groups (initially, sexually promiscuous men who have sex with men). By 1978, the prevalence of HIV-1 among gay male residents of New York and San Francisco was estimated at 5%, suggesting that several thousand individuals in the country had been infected.[192]

Society and culture

Stigma

AIDS stigma exists around the world in a variety of ways, including ostracism, rejection, discrimination and avoidance of HIV infected people; compulsory HIV testing without prior consent or protection of confidentiality; violence against HIV infected individuals or people who are perceived to be infected with HIV; and the quarantine of HIV infected individuals.[193] Stigma-related violence or the fear of violence prevents many people from seeking HIV testing, returning for their results, or securing treatment, possibly turning what could be a manageable chronic illness into a death sentence and perpetuating the spread of HIV.[194]

AIDS stigma has been further divided into the following three categories:

- Instrumental AIDS stigma—a reflection of the fear and apprehension that are likely to be associated with any deadly and transmissible illness.[195]

- Symbolic AIDS stigma—the use of HIV/AIDS to express attitudes toward the social groups or lifestyles perceived to be associated with the disease.[195]

- Courtesy AIDS stigma—stigmatization of people connected to the issue of HIV/AIDS or HIV-positive people.[196]

Often, AIDS stigma is expressed in conjunction with one or more other stigmas, particularly those associated with homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity, prostitution, and intravenous drug use.[197]

In many developed countries, there is an association between AIDS and homosexuality or bisexuality, and this association is correlated with higher levels of sexual prejudice such as anti-homosexual/bisexual attitudes.[198] There is also a perceived association between AIDS and all male-male sexual behavior, including sex between uninfected men.[195] However, the dominant mode of spread worldwide for HIV remains heterosexual transmission.[199]

Economic impact

Changes in life expectancy in some hard-hit African countries. Botswana Zimbabwe Kenya South Africa Uganda

HIV/AIDS affects the economics of both individuals and countries.[162] The gross domestic product of the most affected countries has decreased due to the lack of human capital.[162][200] Without proper nutrition, health care and medicine, large numbers of people die from AIDS-related complications. They will not only be unable to work, but will also require significant medical care. It is estimated that as of 2007 there were 12 million AIDS orphans.[162] Many are cared for by elderly grandparents.[201]

By affecting mainly young adults, AIDS reduces the taxable population, in turn reducing the resources available for public expenditures such as education and health services not related to AIDS resulting in increasing pressure for the state’s finances and slower growth of the economy. This causes a slower growth of the tax base, an effect that is reinforced if there are growing expenditures on treating the sick, training (to replace sick workers), sick pay and caring for AIDS orphans. This is especially true if the sharp increase in adult mortality shifts the responsibility and blame from the family to the government in caring for these orphans.[201]

At the household level, AIDS causes both loss of income and increased spending on healthcare. A study in Côte d’Ivoire showed that households with an HIV/AIDS patient, spent twice as much on medical expenses as other households. This additional expenditure also leaves less income to spend on education and other personal or family investment.[202]

Religion and AIDS

The topic of religion and AIDS has become highly controversial in the past twenty years, primarily because some religious authorities have publicly declared their opposition to the use of condoms.[203][204] The religious approach to prevent the spread of AIDS according to a report by American health expert Matthew Hanley titled The Catholic Church and the Global Aids Crisis argues that cultural changes are needed including a re-emphasis on fidelity within marriage and sexual abstinence outside of it.[204]

Some religious organisations have claimed that prayer can cure HIV/AIDS. In 2011, the BBC reported that some churches in London were claiming that prayer would cure AIDS, and the Hackney-based Centre for the Study of Sexual Health and HIV reported that several people stopped taking their medication, sometimes on the direct advice of their pastor, leading to a number of deaths.[205] The Synagogue Church Of All Nations advertise an “anointing water” to promote God’s healing, although the group deny advising people to stop taking medication.[205]

Media portrayal

One of the first high-profile cases of AIDS was the American Rock Hudson, a gay actor who had been married and divorced earlier in life, who died on 2 October 1985 having announced that he was suffering from the virus on 25 July that year. He had been diagnosed during 1984.[206] A notable British casualty of AIDS that year was Nicholas Eden, a gay politician and son of the late prime minister Anthony Eden.[207] On November 24, 1991, the virus claimed the life of British rock star Freddie Mercury, lead singer of the band Queen, who died from an AIDS related illness having only revealed the diagnosis on the previous day.[208] However he had been diagnosed as HIV positive during 1987.[209] One of the first high-profile heterosexual cases of the virus was Arthur Ashe, the American tennis player. He was diagnosed as HIV positive on 31 August 1988, having contracted the virus from blood transfusions during heart surgery earlier in the 1980s. Further tests within 24 hours of the initial diagnosis revealed that Ashe had AIDS, but he did not tell the public about his diagnosis until April 1992.[210] He died, aged 49, as a result on 6 February 1993.[211]

Therese Frare’s photograph of gay activist David Kirby, as he lay dying from AIDS while surrounded by family, was taken in April 1990. LIFE magazine said the photo became the one image “most powerfully identified with the HIV/AIDS epidemic.” The photo was displayed in LIFE magazine, was the winner of the World Press Photo, and acquired worldwide notoriety after being used in a United Colors of Benetton advertising campaign in 1992.[212] In 1996, Johnson Aziga a Ugandan-born immigrant Canadian was diagnosed as a HIV-positive, but then he had unprotected sex with 11 women without telling them he has HIV. Since 2003, seven of them were infected with HIV, and two of them died of complications of AIDS.[213][214] At last Aziga was convicted of first-degree murder and be liable to a life sentence.[215]

Denial, conspiracies, and misconceptions

A small group of individuals continue to dispute the connection between HIV and AIDS,[216] the existence of HIV itself, or the validity of HIV testing and treatment methods.[217][218] These claims, known as AIDS denialism, have been examined and rejected by the scientific community.[219] However, they have had a significant political impact, particularly in South Africa, where the government’s official embrace of AIDS denialism (1999–2005) was responsible for its ineffective response to that country’s AIDS epidemic, and has been blamed for hundreds of thousands of avoidable deaths and HIV infections.[220][221][222] Operation INFEKTION was a worldwide Soviet active measures operation to spread information that the United States had created HIV/AIDS. Surveys show that a significant number of people believed – and continue to believe – in such claims.[223]

There are many misconceptions about HIV and AIDS. Three of the most common are that AIDS can spread through casual contact, that sexual intercourse with a virgin will cure AIDS, and that HIV can infect only homosexual men and drug users. Other misconceptions are that any act of anal intercourse between two uninfected gay men can lead to HIV infection, and that open discussion of homosexuality and HIV in schools will lead to increased rates of homosexuality and AIDS.[224][225]

Research

HIV/AIDS research includes all medical research which attempts to prevent, treat, or cure HIV/AIDS along with fundamental research about the nature of HIV as an infectious agent and AIDS as the disease caused by HIV.

HIV/AIDS research includes following the usual advice given by doctors in responding to HIV. The most universally recommended method for the prevention of HIV/AIDS is to avoid blood-to-blood contact between people and to otherwise practice safe sex. The most recommended method for treating HIV is for HIV-positive people to receive attention from a doctor who would coordinate the patient’s management of HIV/AIDS. There is no cure for HIV/AIDS.

Many governments and research institutions participate in HIV/AIDS research. This research includes behavioral health interventions such as sex education, and drug development, such as research into microbicides for sexually transmitted diseases, HIV vaccines, and antiretroviral drugs. Other medical research areas include the topics of pre-exposure prophylaxis, post-exposure prophylaxis, and Circumcision and HIV.

Notes

- ^ Sepkowitz KA (June 2001). “AIDS—the first 20 years”. N. Engl. J. Med. 344 (23): 1764–72. doi:10.1056/NEJM200106073442306. PMID 11396444.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Markowitz, edited by William N. Rom ; associate editor, Steven B. (2007). Environmental and occupational medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 745. ISBN 978-0-7817-6299-1.

- ^ “HIV and Its Transmission”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved May 23, 2006.

- ^ a b Sharp, PM; Hahn, BH (2011 Sep). “Origins of HIV and the AIDS Pandemic”. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 1 (1): a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC 3234451. PMID 22229120.

- ^ Gallo RC (2006). “A reflection on HIV/AIDS research after 25 years”. Retrovirology 3: 72. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-3-72. PMC 1629027. PMID 17054781.

- ^ a b “Global Report Fact Sheet”. UNAIDS. 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f UNAIDS 2011 pg. 1–10

- ^ a b Kallings LO (2008). “The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS”. J Intern Med 263 (3): 218–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01910.x. PMID 18205765.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f Mandell, Bennett, and Dolan (2010). Chapter 121.

- ^ a b c “Stages of HIV”. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Dec 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2007. pp. 6–16. ISBN 978-92-4-159562-9.

- ^ Diseases and disorders.. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish. 2008. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7614-7771-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mandell, Bennett, and Dolan (2010). Chapter 118.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Vogel, M; Schwarze-Zander, C; Wasmuth, JC; Spengler, U; Sauerbruch, T; Rockstroh, JK (2010 Jul). “The treatment of patients with HIV”. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international 107 (28–29): 507–15; quiz 516. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0507. PMC 2915483. PMID 20703338.

- ^ Evian, Clive (2006). Primary HIV/AIDS care: a practical guide for primary health care personnel in a clinical and supportive setting (Updated 4th ed.). Houghton [South Africa]: Jacana. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-77009-198-6.

- ^ Radiology of AIDS. Berlin [u.a.]: Springer. 2001. p. 19. ISBN 978-3-540-66510-6.

- ^ Elliott, Tom (2012). Lecture Notes: Medical Microbiology and Infection. John Wiley & Sons. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-118-37226-5.

- ^ a b Blankson, JN (2010 Mar). “Control of HIV-1 replication in elite suppressors”. Discovery medicine 9 (46): 261–6. PMID 20350494.

- ^ Walker, BD (2007 Aug–Sep). “Elite control of HIV Infection: implications for vaccines and treatment.”. Topics in HIV medicine : a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA 15 (4): 134–6. PMID 17720999.

- ^ Holmes CB, Losina E, Walensky RP, Yazdanpanah Y, Freedberg KA (2003). “Review of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related opportunistic infections in sub-Saharan Africa”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36 (5): 656–662. doi:10.1086/367655. PMID 12594648.

- ^ Chu, C; Selwyn, PA (2011-02-15). “Complications of HIV infection: a systems-based approach”. American family physician 83 (4): 395–406. PMID 21322514.

- ^ a b c d e Mandell, Bennett, and Dolan (2010). Chapter 169.

- ^ “AIDS”. MedlinePlus. A.D.A.M. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Sestak K (July 2005). “Chronic diarrhea and AIDS: insights into studies with non-human primates”. Curr. HIV Res. 3 (3): 199–205. doi:10.2174/1570162054368084. PMID 16022653.

- ^ a b Smith, DK; Grohskopf, LA; Black, RJ; Auerbach, JD; Veronese, F; Struble, KA; Cheever, L; Johnson, M; Paxton, LA; Onorato, IM; Greenberg, AE; U.S. Department of Health and Human, Services (2005 Jan 21). “Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.”. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control 54 (RR-2): 1–20. PMID 15660015.

- ^ Coovadia H (2004). “Antiretroviral agents—how best to protect infants from HIV and save their mothers from AIDS”. N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (3): 289–292. doi:10.1056/NEJMe048128. PMID 15247337.

- ^ a b c d Kripke, C (2007 Aug 1). “Antiretroviral prophylaxis for occupational exposure to HIV.”. American family physician 76 (3): 375–6. PMID 17708137.

- ^ a b c d Dosekun, O; Fox, J (2010 Jul). “An overview of the relative risks of different sexual behaviours on HIV transmission.”. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS 5 (4): 291–7. doi:10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a88a3. PMID 20543603.

- ^ Cunha, Burke (2012). Antibiotic Essentials 2012 (11 ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 303. ISBN 9781449693831.

- ^ a b Boily, MC; Baggaley, RF; Wang, L; Masse, B; White, RG; Hayes, RJ; Alary, M (2009 Feb). “Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies.”. The Lancet infectious diseases 9 (2): 118–29. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0. PMID 19179227.

- ^ Baggaley, RF; White, RG; Boily, MC (2008 Dec). “Systematic review of orogenital HIV-1 transmission probabilities.”. International Journal of Epidemiology 37 (6): 1255–65. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn151. PMC 2638872. PMID 18664564.

- ^ van der Kuyl, AC; Cornelissen, M (2007-09-24). “Identifying HIV-1 dual infections”. Retrovirology 4: 67. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-4-67. PMC 2045676. PMID 17892568.

- ^ a b “HIV in the United States: An Overview”. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Boily MC, Baggaley RF, Wang L, Masse B, White RG, Hayes RJ, Alary M (February 2009). “Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies”. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 9 (2): 118–129. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0. PMID 19179227.

- ^ Beyrer, C; Baral, SD; van Griensven, F; Goodreau, SM; Chariyalertsak, S; Wirtz, AL; Brookmeyer, R (2012 Jul 28). “Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men.”. Lancet 380 (9839): 367–77. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. PMID 22819660.

- ^ Yu, M; Vajdy, M (2010 Aug). “Mucosal HIV transmission and vaccination strategies through oral compared with vaginal and rectal routes”. Expert opinion on biological therapy 10 (8): 1181–95. doi:10.1517/14712598.2010.496776. PMC 2904634. PMID 20624114.

- ^ Stürchler, Dieter A. (2006). Exposure a guide to sources of infections. Washington, DC: ASM Press. p. 544. ISBN 9781555813765.

- ^ al.], edited by Richard Pattman … [et (2010). Oxford handbook of genitourinary medicine, HIV, and sexual health (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780199571666.

- ^ a b c Dosekun, O; Fox, J (2010 Jul). “An overview of the relative risks of different sexual behaviours on HIV transmission”. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS 5 (4): 291–7. doi:10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a88a3. PMID 20543603.

- ^ a b Ng, BE; Butler, LM; Horvath, T; Rutherford, GW (2011-03-16). “Population-based biomedical sexually transmitted infection control interventions for reducing HIV infection”. In Butler, Lisa M. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD001220. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001220.pub3. PMID 21412869.

- ^ Anderson, J (2012 Feb). “Women and HIV: motherhood and more”. Current opinion in infectious diseases 25 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834ef514. PMID 22156896.

- ^ Klimas, N; Koneru, AO; Fletcher, MA (2008 Jun). “Overview of HIV”. Psychosomatic Medicine 70 (5): 523–30. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817ae69f. PMID 18541903.

- ^ Draughon, JE; Sheridan, DJ (2012). “Nonoccupational post exposure prophylaxis following sexual assault in industrialized low-HIV-prevalence countries: a review”. Psychology, health & medicine 17 (2): 235–54. doi:10.1080/13548506.2011.579984. PMID 22372741.

- ^ a b Baggaley, RF; Boily, MC; White, RG; Alary, M (2006-04-04). “Risk of HIV-1 transmission for parenteral exposure and blood transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. AIDS (London, England) 20 (6): 805–12. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000218543.46963.6d. PMID 16549963.

- ^ “Will I need a blood transfusion?”. NHS patient information. National Health Services. 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ UNAIDS 2011 pg. 60–70

- ^ “Blood safety … for too few”. WHO. 2001. Retrieved January 17, 2006.

- ^ a b c Reid, SR (2009-08-28). “Injection drug use, unsafe medical injections, and HIV in Africa: a systematic review”. Harm reduction journal 6: 24. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-24. PMC 2741434. PMID 19715601.

- ^ a b “Basic Information about HIV and AIDS”. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. April 2012.

- ^ “Why Mosquitoes Cannot Transmit AIDS [HIV virus]”. Rci.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Coutsoudis, A; Kwaan, L; Thomson, M (2010 Oct). “Prevention of vertical transmission of HIV-1 in resource-limited settings”. Expert review of anti-infective therapy 8 (10): 1163–75. doi:10.1586/eri.10.94. PMID 20954881.

- ^ “Fluids of transmission”. AIDS.gov. United States Department of Health and Human Services. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ a b Thorne, C; Newell, ML (2007 Jun). “HIV”. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine 12 (3): 174–81. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.009. PMID 17321814.

- ^ Alimonti JB, Ball TB, Fowke KR (2003). “Mechanisms of CD4+ T lymphocyte cell death in human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS”. J. Gen. Virol. 84 (7): 1649–1661. doi:10.1099/vir.0.19110-0. PMID 12810858.

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2002). “61.0.6. Lentivirus”. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2006-04-18. Retrieved 2012-06-25.

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2002). “61. Retroviridae”. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2006-06-29. Retrieved 2012-06-25.

- ^ Lévy, J. A. (1993). “HIV pathogenesis and long-term survival”. AIDS 7 (11): 1401–10. doi:10.1097/00002030-199311000-00001. PMID 8280406.

- ^ Smith, Johanna A.; Daniel, René (Division of Infectious Diseases, Center for Human Virology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia) (2006). “Following the path of the virus: the exploitation of host DNA repair mechanisms by retroviruses”. ACS Chem Biol 1 (4): 217–26. doi:10.1021/cb600131q. PMID 17163676.

- ^ Martínez, edited by Miguel Angel (2010). RNA interference and viruses : current innovations and future trends. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781904455561.

- ^ Immunology, infection, and immunity. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. 2004. p. 550. ISBN 9781555812461.

- ^ Gilbert, PB et al. (28 February 2003). “Comparison of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infectivity from a prospective cohort study in Senegal”. Statistics in Medicine 22 (4): 573–593. doi:10.1002/sim.1342. PMID 12590415.

- ^ a b Reeves, J. D. and Doms, R. W (2002). “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 2”. J. Gen. Virol. 83 (Pt 6): 1253–65. doi:10.1099/vir.0.18253-0. PMID 12029140.

- ^ Piatak, M., Jr, Saag, M. S., Yang, L. C., Clark, S. J., Kappes, J. C., Luk, K. C., Hahn, B. H., Shaw, G. M. and Lifson, J.D. (1993). “High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR”. Science 259 (5102): 1749–1754. Bibcode:1993Sci…259.1749P. doi:10.1126/science.8096089. PMID 8096089.

- ^ Pantaleo G, Demarest JF, Schacker T, Vaccarezza M, Cohen OJ, Daucher M, Graziosi C, Schnittman SS, Quinn TC, Shaw GM, Perrin L, Tambussi G, Lazzarin A, Sekaly RP, Soudeyns H, Corey L, Fauci AS. (1997). “The qualitative nature of the primary immune response to HIV infection is a prognosticator of disease progression independent of the initial level of plasma viremia”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 94 (1): 254–258. Bibcode:1997PNAS…94..254P. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.1.254. PMC 19306. PMID 8990195.

- ^ Guss DA (1994). “The acquired immune deficiency syndrome: an overview for the emergency physician, Part 1”. J Emerg Med 12 (3): 375–84. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(94)90281-X. PMID 8040596.

- ^ Hel Z, McGhee JR, Mestecky J (June 2006). “HIV infection: first battle decides the war”. Trends Immunol. 27 (6): 274–81. doi:10.1016/j.it.2006.04.007. PMID 16679064.

- ^ Arie J. Zuckerman et al. (eds) (2007). Principles and practice of clinical virology (6th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. p. 905. ISBN 978-0-470-51799-4.

- ^ Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Horowitz A, Hurley A, Hogan C, Boden D, Racz P, Markowitz M (September 2004). “Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T cells from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract”. J. Exp. Med. 200 (6): 761–70. doi:10.1084/jem.20041196. PMC 2211967. PMID 15365095.

- ^ Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, Price DA, Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, Nguyen PL, Khoruts A, Larson M, Haase AT, Douek DC (September 2004). “CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract”. J. Exp. Med. 200 (6): 749–59. doi:10.1084/jem.20040874. PMC 2211962. PMID 15365096.

- ^ a b editor, Julio Aliberti, (2011). Control of Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses During Infectious Diseases.. New York, NY: Springer Verlag. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4614-0483-5.

- ^ Appay V, Sauce D (January 2008). “Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences”. J. Pathol. 214 (2): 231–41. doi:10.1002/path.2276. PMID 18161758.

- ^ Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC (December 2006). “Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection”. Nat. Med. 12 (12): 1365–71. doi:10.1038/nm1511. PMID 17115046.

- ^ a b Kellerman, S; Essajee, S (2010 Jul 20). “HIV testing for children in resource-limited settings: what are we waiting for?”. PLoS medicine 7 (7): e1000285. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000285. PMC 2907270. PMID 20652012.

- ^ a b c UNAIDS 2011 pg. 70–80

- ^ a b c d Schneider, E; Whitmore, S; Glynn, KM; Dominguez, K; Mitsch, A; McKenna, MT; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC) (2008-12-05). “Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents, and children aged <18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to <13 years–United States, 2008”. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control 57 (RR–10): 1–12. PMID 19052530.

- ^ Crosby, R; Bounse, S (2012 Mar). “Condom effectiveness: where are we now?”. Sexual health 9 (1): 10–7. doi:10.1071/SH11036. PMID 22348628.

- ^ “Condom Facts and Figures”. WHO. August 2003. Retrieved January 17, 2006.

- ^ Gallo, MF; Kilbourne-Brook, M; Coffey, PS (2012 Mar). “A review of the effectiveness and acceptability of the female condom for dual protection”. Sexual health 9 (1): 18–26. doi:10.1071/SH11037. PMID 22348629.

- ^ a b Celum, C; Baeten, JM (2012 Feb). “Tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: evolving evidence”. Current opinion in infectious diseases 25 (1): 51–7. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834ef5ef. PMC 3266126. PMID 22156901.

- ^ Baptista, M; Ramalho-Santos, J (2009-11-01). “Spermicides, microbicides and antiviral agents: recent advances in the development of novel multi-functional compounds”. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry 9 (13): 1556–67. doi:10.2174/138955709790361548. PMID 20205637.

- ^ Siegfried, N; Muller, M; Deeks, JJ; Volmink, J (2009-04-15). “Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men”. In Siegfried, Nandi. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD003362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. PMID 19370585.

- ^ “WHO and UNAIDS announce recommendations from expert consultation on male circumcision for HIV prevention”. World Health Organization. Mar 28, 2007.

- ^ Larke, N (2010 May 27 – Jun 9). “Male circumcision, HIV and sexually transmitted infections: a review”. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing) 19 (10): 629–34. PMID 20622758.

- ^ Eaton, L; Kalichman, SC (2009 Nov). “Behavioral aspects of male circumcision for the prevention of HIV infection”. Current HIV/AIDS reports 6 (4): 187–93. doi:10.1007/s11904-009-0025-9. PMID 19849961.(subscription required)

- ^ Kim, HH; Li, PS, Goldstein, M (2010 Nov). “Male circumcision: Africa and beyond?”. Current opinion in urology 20 (6): 515–9. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b21. PMID 20844437.

- ^ Templeton, DJ; Millett, GA, Grulich, AE (2010 Feb). “Male circumcision to reduce the risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men”. Current opinion in infectious diseases 23 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328334e54d. PMID 19935420.

- ^ Wiysonge, CS.; Kongnyuy, EJ.; Shey, M.; Muula, AS.; Navti, OB.; Akl, EA.; Lo, YR. (2011). “Male circumcision for prevention of homosexual acquisition of HIV in men”. In Wiysonge, Charles Shey. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (6): CD007496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007496.pub2. PMID 21678366.

- ^ Eaton LA, Kalichman S (December 2007). “Risk compensation in HIV prevention: implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies”. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 4 (4): 165–72. doi:10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. PMC 2937204. PMID 18366947.

- ^ Underhill K, Operario D, Montgomery P (2008). “Abstinence-only programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries”. In Operario, Don. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005421. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005421.pub2. PMID 17943855.

- ^ Tolli, MV (2012-05-28). “Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention, adolescent pregnancy prevention and sexual health promotion for young people: a systematic review of European studies”. Health education research. doi:10.1093/her/cys055. PMID 22641791.

- ^ Ljubojević, S; Lipozenčić, J (2010). “Sexually transmitted infections and adolescence”. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC 18 (4): 305–10. PMID 21251451.

- ^ Patel VL, Yoskowitz NA, Kaufman DR, Shortliffe EH (2008). “Discerning patterns of human immunodeficiency virus risk in healthy young adults”. Am J Med 121 (4): 758–764. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.022. PMC 2597652. PMID 18724961.

- ^ Anglemyer, A; Rutherford, GW; Baggaley, RC; Egger, M; Siegfried, N (2011-08-10). “Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples”. In Rutherford, George W. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (8): CD009153. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009153.pub2. PMID 21833973.

- ^ Chou R, Selph S, Dana T, et al. (November 2012). “Screening for HIV: systematic review to update the 2005 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation”. Ann. Intern. Med. 157 (10): 706–18. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00007. PMID 23165662.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (August 1987). “Recommendations for prevention of HIV transmission in health-care settings”. MMWR 36 (Suppl 2): 1S–18S. PMID 3112554.

- ^ a b Kurth, AE; Celum, C; Baeten, JM; Vermund, SH; Wasserheit, JN (2011 Mar). “Combination HIV prevention: significance, challenges, and opportunities”. Current HIV/AIDS reports 8 (1): 62–72. doi:10.1007/s11904-010-0063-3. PMC 3036787. PMID 20941553.

- ^ MacArthur, G. J.; Minozzi, S.; Martin, N.; Vickerman, P.; Deren, S.; Bruneau, J.; Degenhardt, L.; Hickman, M. (4 October 2012). “Opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis”. BMJ 345 (oct03 3): e5945–e5945. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5945.

- ^ a b c [No authors listed] (April 2012). “HIV exposure through contact with body fluids”. Prescrire Int 21 (126): 100–1, 103–5. PMID 22515138.

- ^ Linden, JA (2011-09-01). “Clinical practice. Care of the adult patient after sexual assault”. The New England Journal of Medicine 365 (9): 834–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1102869. PMID 21879901.

- ^ Young, TN; Arens, FJ; Kennedy, GE; Laurie, JW; Rutherford, G (2007-01-24). “Antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for occupational HIV exposure”. In Young, Taryn. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD002835. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002835.pub3. PMID 17253483.

- ^ Siegfried, N; van der Merwe, L; Brocklehurst, P; Sint, TT (2011-07-06). “Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection”. In Siegfried, Nandi. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (7): CD003510. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003510.pub3. PMID 21735394.

- ^ “WHO HIV and Infant Feeding Technical Consultation Held on behalf of the Inter-agency Task Team (IATT) on Prevention of HIV – Infections in Pregnant Women, Mothers and their Infants – Consensus statement” (PDF). October 25–27, 2006. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ^ Horvath, T; Madi, BC; Iuppa, IM; Kennedy, GE; Rutherford, G; Read, JS (2009-01-21). “Interventions for preventing late postnatal mother-to-child transmission of HIV”. In Horvath, Tara. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD006734. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006734.pub2. PMID 19160297.

- ^ UNAIDS (May 18, 2012). “The quest for an HIV vaccine”.

- ^ Reynell, L; Trkola, A (2012-03-02). “HIV vaccines: an attainable goal?”. Swiss medical weekly 142: w13535. doi:10.4414/smw.2012.13535. PMID 22389197.

- ^ U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General (March 21, 2011). “HIV Vaccine Trial in Thai Adults”. ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General (June 2, 2010). “Follow up of Thai Adult Volunteers With Breakthrough HIV Infection After Participation in a Preventive HIV Vaccine Trial”. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- ^ May, MT; Ingle, SM (2011 Dec). “Life expectancy of HIV-positive adults: a review”. Sexual health 8 (4): 526–33. doi:10.1071/SH11046. PMID 22127039.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization. 2010. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-92-4-159976-4.

- ^ Sax, PE; Baden, LR (2009-04-30). “When to start antiretroviral therapy—ready when you are?”. The New England Journal of Medicine 360 (18): 1897–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMe0902713. PMID 19339713.

- ^ Siegfried, N; Uthman, OA; Rutherford, GW (2010-03-17). “Optimal time for initiation of antiretroviral therapy in asymptomatic, HIV-infected, treatment-naive adults”. In Siegfried, Nandi. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD008272. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008272.pub2. PMID 20238364.

- ^ Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents (2009-12-01). Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. United States Department of Health and Human Services. p. i.

- ^ When To Start, Consortium; Sterne, JA; May, M; Costagliola, D; de Wolf, F; Phillips, AN; Harris, R; Funk, MJ; Geskus, RB; Gill, J; Dabis, F; Miró, JM; Justice, AC; Ledergerber, B; Fätkenheuer, G; Hogg, RS; Monforte, AD; Saag, M; Smith, C; Staszewski, S; Egger, M; Cole, SR (2009-04-18). “Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies”. Lancet 373 (9672): 1352–63. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60612-7. PMC 2670965. PMID 19361855.

- ^ Beard, J; Feeley, F; Rosen, S (2009 Nov). “Economic and quality of life outcomes of antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in developing countries: a systematic literature review”. AIDS care 21 (11): 1343–56. doi:10.1080/09540120902889926. PMID 20024710.

- ^ Orrell, C (2005 Nov). “Antiretroviral adherence in a resource-poor setting”. Current HIV/AIDS reports 2 (4): 171–6. doi:10.1007/s11904-005-0012-8. PMID 16343374.

- ^ Malta, M; Strathdee, SA; Magnanini, MM; Bastos, FI (2008 Aug). “Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review”. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 103 (8): 1242–57. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02269.x. PMID 18855813.

- ^ Nachega, JB; Marconi, VC; van Zyl, GU; Gardner, EM; Preiser, W; Hong, SY; Mills, EJ; Gross, R (2011 Apr). “HIV treatment adherence, drug resistance, virologic failure: evolving concepts”. Infectious disorders drug targets 11 (2): 167–74. PMID 21406048.

- ^ Orsi, F; d’almeida, C (2010 May). “Soaring antiretroviral prices, TRIPS and TRIPS flexibilities: a burning issue for antiretroviral treatment scale-up in developing countries”. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS 5 (3): 237–41. doi:10.1097/COH.0b013e32833860ba. PMID 20539080.