Wikipédia

George Orson Welles (//; May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, writer and producer who worked in theater, radio and film. He is best remembered for his innovative work in all three media: in theatre, most notably Caesar (1937), a groundbreaking Broadway adaptation of Julius Caesar; in radio, the debut of the Mercury Theatre, whose The War of the Worlds (1938), is one of the most famous broadcasts in the history of radio; and in film, Citizen Kane (1941), consistently ranked as one of the all-time greatest films.

After directing a number of high-profile stage productions in his early twenties, including an innovative adaptation of Macbeth and The Cradle Will Rock, Welles found national and international fame as the director and narrator of a 1938 radio adaptation of H. G. Wells‘ novel The War of the Worlds performed for the radio anthology series The Mercury Theatre on the Air. It reportedly caused widespread panic when listeners thought that an invasion by extraterrestrial beings was occurring. Although some contemporary sources claim these reports of panic were mostly false and overstated,[2] they rocketed Welles to notoriety.

His first film was Citizen Kane (1941), which he co-wrote, produced, directed, and starred in as Charles Foster Kane. Welles was an outsider to the studio system and directed only 13 full-length films in his career. Because of this, he struggled for creative control from the major film studios, and his films were either heavily edited or remained unreleased. His distinctive directorial style featured layered and nonlinear narrative forms, innovative uses of lighting such as chiaroscuro, unusual camera angles, sound techniques borrowed from radio, deep focus shots, and long takes. He has been praised as a major creative force and as “the ultimate auteur.”[3]:6 Welles followed up Citizen Kane with critically acclaimed films including The Magnificent Ambersons in 1942 and Touch of Evil in 1958.

In 2002, Welles was voted the greatest film director of all time in two British Film Institute polls among directors and critics,[4][5] and a wide survey of critical consensus, best-of lists, and historical retrospectives calls him the most acclaimed director of all time.[6] Well known for his baritone voice,[7] Welles was a well-regarded actor in radio and film, a celebrated Shakespearean stage actor, and an accomplished magician noted for presenting troop variety shows in the war years.

Early life

George Orson Welles was born May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin, son of Richard Hodgdon Head Welles (b. 1873, Missouri, d. December 28, 1930, Chicago, Illinois) and Beatrice (née Ives; b. 1882 or 1883, Springfield, Illinois, d. May 10, 1924, Chicago).[8] He was named after his paternal great-grandfather, influential Kenosha attorney Orson S. Head, and his brother George Head,[9]:37 and was raised Roman Catholic.[10]

Despite the Head family’s affluence, Welles encountered hardship in childhood. His parents separated and moved to Chicago in 1919. His father, who made a fortune as the inventor of a popular bicycle lamp,[11] became an alcoholic and stopped working. Welles’s mother, a concert pianist, played during lectures by Dudley Crafts Watson at the Chicago Art Institute to support her son and herself; the oldest Welles boy, “Dickie”, was institutionalized at an early age because he had learning difficulties. Beatrice died of hepatitis in a Chicago hospital[12]:3–5 May 10, 1924, at the age of 43, just after Welles’s ninth birthday.[13]:326

After his mother’s death Welles ceased pursuing music. It was decided that he would spend the summer with the Watson family at a private art colony in Wyoming, New York, established by Lydia Avery Coonley Ward.[1]:8 There he played and became friends with the children of the Aga Khan, including the 12-year-old Prince Aly Khan. Then, in what Welles later described as “a hectic period” in his life, he lived in a Chicago apartment with both his father and Dr. Maurice Bernstein, a Chicago physician who had been a close friend of both his parents. Welles briefly attended public school[14]:133 before his alcoholic father left business altogether and took him along on his travels to Jamaica and the Far East. When they returned they settled in a hotel in Grand Detour, Illinois, that was owned by his father. When the hotel burned down Welles and his father took to the road again.[1]:9

“During the three years that Orson lived with his father, some observers wondered who took care of whom”, wrote biographer Frank Brady.[1]:9

“In some ways, he was never really a young boy, you know,” said Roger Hill, who became Welles’s teacher and lifelong friend.[15]:24

Welles briefly attended public school in Madison, Wisconsin, enrolled in the fourth grade.[1]:9 On September 15, 1926, he entered the Todd School for Boys,[14]:3 an expensive independent school in Woodstock, Illinois, that his older brother had attended for ten years until he was expelled for misbehavior.[1]:10 At Todd School Welles came under the influence of Roger Hill, a teacher who was later Todd’s headmaster. Hill provided Welles with an ad hoc educational environment that proved invaluable to his creative experience, allowing Welles to concentrate on subjects that interested him. Welles performed and staged theatrical experiments and productions there.

“Todd provided Welles with many valuable experiences”, wrote critic Richard France. “He was able to explore and experiment in an atmosphere of acceptance and encouragement. In addition to a theater the school’s own radio station was at his disposal.”[16]:27 Welles’s first radio performance was on the Todd station, an adaptation of Sherlock Holmes that he also wrote.[12]:7

On December 28, 1930, when Welles was 15, his father died at the age of 58, alone in a hotel in Chicago. His will left it to Orson to name his guardian. When Roger Hill declined, Welles chose Maurice Bernstein.[17]:71–72

Following graduation from Todd in May 1931,[14]:3 Welles was awarded a scholarship to Harvard University. Rather than enrolling, he chose travel. Later, he studied for a time at the Art Institute of Chicago.[18] He returned a number of times to Woodstock to direct his alma mater’s student productions.

Early career (1931–1935)

After his father’s death, Welles traveled to Europe using a small inheritance. Welles said that while on a walking and painting trip through Ireland, he strode into the Gate Theatre in Dublin and claimed he was a Broadway star. The manager of Gate, Hilton Edwards, later said he had not believed him but was impressed by his brashness and an impassioned quality in his audition.[19]:134 Welles made his stage debut at the Gate Theatre on October 13, 1931, appearing in Ashley Dukes‘s adaptation of Jew Suss as Duke Karl Alexander of Württemberg. He performed small supporting roles in subsequent Gate productions, and he produced and designed productions of his own in Dublin. In March 1932 Welles performed in W. Somerset Maugham‘s The Circle at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre and travelled to London to find additional work in the theatre. Unable to obtain a work permit, he returned to the U.S.[13]:327–330

Welles found his fame ephemeral and turned to a writing project at Todd School that would become the immensely successful, first entitled Everybody’s Shakespeare and subsequently, The Mercury Shakespeare. Welles traveled to North Africa while working on thousands of illustrations for the Everybody’s Shakespeare series of educational books, a series that remained in print for decades.

In 1933, Roger and Hortense Hill invited Welles along to a party in Chicago, where Welles met Thornton Wilder. Wilder arranged for Welles to meet Alexander Woollcott in New York, in order that he be introduced to Katharine Cornell, who was assembling a repertory theatre company. Cornell’s husband, director Guthrie McClintic, immediately put Welles under contract and cast him in three plays.[1]:46–49 The Barretts of Wimpole Street and Candida toured in repertory for 36 weeks beginning in November 1933, with the first of more than 200 performances taking place in Buffalo, New York.[13]:330–331

In 1934, Welles got his first job on radio — on The American School of the Air — through actor-director Paul Stewart, who introduced him to director Knowles Entrikin.[13]:331 That summer Welles staged a drama festival with the Todd School in Woodstock, Illinois, inviting Micheál Mac Liammóir and Hilton Edwards from Dublin’s Gate Theatre to appear along with New York stage luminaries in productions including Trilby, Hamlet, The Drunkard and Tsar Paul. At the old firehouse in Woodstock he also shot his first film, an eight-minute short titled The Hearts of Age.[13]:330–331

Katharine Cornell’s company began a 36-week tour of Romeo and Juliet in the fall of 1934, with Welles playing Mercutio. Opening December 20 at the Martin Beck Theatre in New York,[13]:331–332[20] the Broadway production brought the 19-year-old Welles (now playing Tybalt) to the notice of John Houseman, a theatrical producer who was casting the lead role in the debut production of Archibald MacLeish‘s verse play, Panic.[21]:144–158

On November 14, 1934, Welles married Chicago socialite and actress Virginia Nicolson[13]:332 (often misspelled “Nicholson”)[22] in a civil ceremony in New York. To appease the Nicolsons, who were furious at the couple’s elopement, a formal ceremony took place December 23, 1934, at the New Jersey mansion of the bride’s godmother. Welles wore a cutaway borrowed from his friend George Macready.[17]:182

By 1935 Welles was supplementing his earnings in the theater as a radio actor in Manhattan, working with many actors who would later form the core of his Mercury Theatre on programs including America’s Hour, Cavalcade of America, Columbia Workshop and The March of Time.[13]:331–332 “Within a year of his debut Welles could claim membership in that elite band of radio actors who commanded salaries second only to the highest paid movie stars,” wrote critic Richard France.[16]:172

Theatre (1936–1938)

Federal Theatre Project

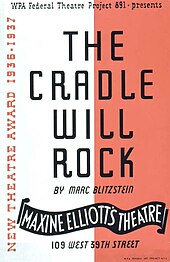

Silkscreen poster for

Macbeth (Anthony Velonis)

Macbeth

In 1936, the Federal Theatre Project (part of Roosevelt‘s Works Progress Administration) put unemployed theater performers and employees to work. Welles was hired by John Houseman and assigned to direct a play for the Federal Theatre Project’s Negro Theater Unit. He offered Macbeth.[23] The production became known as the Voodoo Macbeth, because Welles set it in the Haitian court of King Henri Christophe, with voodoo witch doctors for the three Weird Sisters. Jack Carter played Macbeth. Canada Lee, who two years before had rescued Welles from a potentially dangerous scrape with an armed theater-goer, played Banquo.[24] The incidental music was composed by Virgil Thomson. The play opened April 14, 1936, at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem and was received rapturously. It later toured the nation. When the lead actor, Maurice Ellis, fell ill on tour, Welles quickly boarded an airplane to fly to the location and stepped in to the part, playing in blackface.[25] At 20, Welles was hailed as a prodigy. A few minutes of the Welles production of Macbeth was recorded on film in a 1937 documentary called We Work Again.[26]

Horse Eats Hat

After the success of Macbeth, Welles mounted the farce Horse Eats Hat, an adaptation by Welles and Edwin Denby of Eugène Labiche‘s play, Un Chapeau de Paille d’Italie.[15]:114 The play was presented September 26 – December 5, 1936, at Maxine Elliott’s Theatre, New York.[13]:334 Joseph Cotten was featured in his first starring role.[27]

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

Welles consolidated his “White Hope” reputation with Dr. Faustus, which used light as a prime unifying scenic element in a nearly black stage. Faustus was presented January 8 – May 9, 1937, at Maxine Elliott’s Theatre, New York.[13]:335

The Second Hurricane

In 1937 American composer Aaron Copland chose Welles to direct The Second Hurricane, an operetta with a libretto by Edwin Denby, and one of Copland’s least known works. Presented at the Henry Street Settlement Music School in New York for the benefit of high school students, the production opened April 21, 1937, and ran its scheduled three performances.[13]:337 Among the few adult performers in the production was actor Joseph Cotten, Welles’s longtime friend and collaborator, who was paid $10 for his performance.[28]

The Cradle Will Rock

In 1937, Welles rehearsed Marc Blitzstein‘s political operetta, The Cradle Will Rock. It was originally scheduled to open June 16, 1937, in its first public preview. Because of severe federal cutbacks in the Works Progress projects, the show’s premiere at the Maxine Elliott Theatre was canceled. The theater was locked and guarded to prevent any government-purchased materials from being used for a commercial production of the work. In a last-minute move, Welles announced to waiting ticket-holders that the show was being transferred to the Venice, 20 blocks away. Some cast, and some crew and audience, walked the distance on foot. The union musicians refused to perform in a commercial theater for lower non-union government wages. The actors’ union stated that the production belonged to the Federal Theater Project and could not be performed outside that context without permission. Lacking the participation of the union members, The Cradle Will Rock began with Blitzstein introducing the show and playing the piano accompaniment on stage with some cast members performing from the audience. This impromptu performance was well received by its audience. It afterward played at the Venice for two weeks in the same informal way.

Mercury Theatre

Breaking with the Federal Theatre Project in 1937, Welles and Houseman founded their own repertory company, which they called the Mercury Theatre. The name was inspired by the title of the iconoclastic magazine, The American Mercury.[1]:119–120 Welles became executive producer and the repertory company eventually included actors such as Ray Collins, George Coulouris, Joseph Cotten, Dolores del Río, Agnes Moorehead, Erskine Sanford and Everett Sloane, all of whom worked for Welles for years. The first Mercury Theatre production was a melodramatic edited version of William Shakespeare‘s tragedy Julius Caesar, set in a contemporary frame of fascist Italy. Cinna, the Poet dies at the hands not of a mob but of a secret police force. According to Norman Lloyd, who played Cinna the Poet, “it stopped the show.” The applause lasted more than ten minutes and the production was widely acclaimed.

Caesar opened November 11, 1937, followed by The Shoemaker’s Holiday (January 11, 1938), Heartbreak House (April 29, 1938) and Danton’s Death (November 5, 1938).[29]:344

Radio (1936–1940)

Simultaneously with his work in the theatre, Welles worked extensively in radio as an actor, writer, director and producer, often without credit.[29]:77 Between 1935 and 1937 he was earning as much as $2,000 a week, shuttling between radio studios at such a pace that he would arrive barely in time for a quick scan of his lines before he was on the air. While he was directing the Voodoo Macbeth Welles was dashing between Harlem and midtown Manhattan three times a day to meet his radio commitments.[16]:172

“What didn’t I do on the radio?” Welles reflected in February 1983:

Radio is what I love most of all. The wonderful excitement of what could happen in live radio, when everything that could go wrong did go wrong. I was making a couple of thousand a week, scampering in ambulances from studio to studio, and committing much of what I made to support the Mercury. I wouldn’t want to return to those frenetic 20-hour working day years, but I miss them because they are so irredeemably gone.[14]:53

In addition to continuing as a repertory player on The March of Time, in the fall of 1936 Welles adapted and performed Hamlet in an early two-part episode of CBS Radio‘s Columbia Workshop. His performance as the announcer in the series’ April 1937 presentation of Archibald MacLeish‘s verse drama The Fall of the City was an important development in his radio career[29]:78 and made the 21-year-old Welles an overnight star.[30]

In July 1937, the Mutual Network gave Welles a seven-week series to adapt Les Misérables, which he did with great success. Welles developed the idea of telling stories with first-person narration on the series, which was his first job as a writer-director for radio.[13]:338 Les Misérables was one of Welles’s earliest and finest achievements on radio,[31]:160 and marked the radio debut of the Mercury Theatre.

That September, Mutual chose Welles to play Lamont Cranston, also known as The Shadow. He performed the role anonymously through mid-September 1938.[29]:83[32]

The Mercury Theatre on the Air

After the theatrical successes of the Mercury Theatre, CBS Radio invited Orson Welles to create a summer show for 13 weeks. The series began July 11, 1938, initially titled First Person Singular, with the formula that Welles would play the lead in each show. Some months later the show was called The Mercury Theatre on the Air.[33] The weekly hour-long show presented radio plays based on classic literary works, with original music composed and conducted by Bernard Herrmann.

The War of the Worlds broadcast

The Mercury Theatre’s radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells October 30, 1938, brought Welles instant fame. The combination of the news bulletin form of the performance with the between-breaks dial spinning habits of listeners was later reported to have created widespread confusion among listeners who failed to hear the introduction, although the extent of this confusion has come into question.[2][34][35][36] Panic was reportedly spread among listeners who believed the fictional news reports of a Martian invasion. The myth of the result created by the combination was reported as fact around the world and disparagingly mentioned by Adolf Hitler in a public speech some months later.[37]

Welles’s growing fame drew Hollywood offers, lures that the independent-minded Welles resisted at first. The Mercury Theatre on the Air, which had been a sustaining show (without sponsorship) was picked up by Campbell Soup and renamed The Campbell Playhouse.[38]

The Campbell Playhouse

As a direct result of the front-page headlines Orson Welles generated with his 1938 Halloween production The War of the Worlds, Campbell’s Soup signed on as sponsor. The Mercury Theatre on the Air made its last broadcast December 4, 1938, and The Campbell Playhouse began December 9, 1938.

Welles began commuting from Hollywood to New York for the two Sunday broadcasts of The Campbell Playhouse after signing a film contract with RKO Pictures in August 1939. In November 1939, production of the show moved from New York to Los Angeles.[13]:353

After 20 shows, Campbell began to exercise more creative control and had complete control over story selection. As his contract with Campbell came to an end, Welles chose not to sign on for another season. After the broadcast of March 31, 1940, Welles and Campbell parted amicably.[1]:221–226

Hollywood (1939–1948)

RKO Radio Pictures president George Schaefer eventually offered Welles what generally is considered the greatest contract offered to an untried director: complete artistic control.

After signing a summary agreement with RKO on July 22, Welles signed a full-length 63-page contract August 21, 1939.[13]:353

RKO signed Welles in a two-picture deal; including script, cast, crew and most importantly, final cut, although Welles had a budget limit for his projects. With this contract in hand, Welles (and nearly the whole Mercury Theatre troupe) moved to Hollywood. He commuted weekly to New York to maintain his commitment to The Campbell Playhouse.

Welles toyed with various ideas for his first project for RKO Radio Pictures, settling on an adaptation of Joseph Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness, which he worked on in detail. He planned to film the action with a subjective camera (a technique later used in the Robert Montgomery film Lady in the Lake). When a budget was drawn up, RKO’s enthusiasm cooled because it was greater than the agreed limit. RKO also declined to approve another Welles project, The Smiler With the Knife, based on the Cecil Day-Lewis novel, ostensibly because RKO executives lacked faith in Lucille Ball‘s ability to carry the film as the leading lady.

Welles’s first experience on a Hollywood film was narrator for RKO’s 1940 production of Swiss Family Robinson.[39]

Citizen Kane

Production

RKO, having rejected Welles’s first two movie proposals, agreed on the third offer, Citizen Kane, which Welles co-wrote, produced and directed, also performing the lead role.[40]

Welles found a suitable film project in an idea he conceived with screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, (then writing radio plays for The Campbell Playhouse[41]). Initially titled The American, it eventually became Welles’s first feature film (his most famous and honored role), Citizen Kane (1941).

Mankiewicz based the original outline on an exposé of the life of William Randolph Hearst, whom he knew socially and came to hate, having once been great friends with Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies. Banished from her company because of his perpetual drunkenness, Mankiewicz, a notorious gossip, exacted revenge with his unflattering depiction of Davies in Citizen Kane for which Welles bore most of the criticisms.

Kane’s megalomania was modeled loosely on Robert McCormick, Howard Hughes and Joseph Pulitzer as Welles wanted to create a broad, complex character, intending to show him in the same scenes from several points of view. The use of multiple narrative perspectives in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness influenced the treatment.

Supplying Mankiewicz with 300 pages of notes, Welles urged him to write the first draft screenplay under John Houseman, who was posted to ensure Mankiewicz stayed sober. On Welles’s instruction, Houseman wrote the opening narration as a pastiche of The March of Time newsreels. Orson Welles explained to Peter Bogdanovich about the writers working separately by saying, “I left him on his own finally, because we’d started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine.”[13]:54 Taking these drafts, Welles drastically condensed and rearranged them, then added scenes of his own. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz’s contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, “At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank’s and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own.”[13]:54

Charles Foster Kane is based loosely on areas of Hearst’s life. Nonetheless, autobiographical allusions to Welles were worked in, most noticeably in the treatment of Kane’s childhood and particularly, regarding his guardianship. Welles added features from other famous American lives to create a general and mysterious personality, rather than the narrow journalistic portrait drawn by Mankiewicz, whose first drafts included scandalous claims about the death of film director Thomas Ince.

Once the script was complete, Welles attracted some of Hollywood’s best technicians, including cinematographer Gregg Toland, who walked into Welles’s office and announced he wanted to work on the picture. Welles described Toland as “the fastest cameraman who ever lived.”[40] For the cast, Welles primarily used actors from his Mercury Theatre. He invited suggestions from everyone but only if they were directed through him. Filming Citizen Kane took ten weeks.[40]

Reaction

Mankiewicz handed a copy of the shooting script to his friend, Charles Lederer, husband of Welles’s ex-wife, Virginia Nicolson, and the nephew of Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies. Gossip columnist Hedda Hopper saw a small ad in a newspaper for a preview screening of Citizen Kane and went. Hopper realized immediately that the film was based on features of Hearst’s life. Thus began a struggle, the attempted suppression of Citizen Kane.

Hearst’s media outlets boycotted the film. They exerted enormous pressure on the Hollywood film community by threatening to expose fifteen years of suppressed scandals and the fact that most studio bosses were Jewish. At one point, heads of the major studios jointly offered RKO the cost of the film in exchange for the negative and existing prints, fully intending to burn them. RKO declined, and the film was given a limited release. Hearst intimidated theater chains by threatening to ban advertising for their other films in his papers if they showed Citizen Kane.

The film was well-received critically, with Bosley Crowther, film critic for the New York Times calling it “close to being the most sensational film ever made in Hollywood”.[42] By the time it reached the general public, the publicity had waned. It garnered nine Academy Award nominations (Orson nominated as a producer, director, writer and actor), but won only for Best Original Screenplay, shared by Mankiewicz and Welles. Although it was largely ignored at the Academy Awards, Citizen Kane is now hailed as one of the greatest films ever made. Andrew Sarris called it “the work that influenced the cinema more profoundly than any American film since The Birth of a Nation.”[40]

The delay in its release and uneven distribution contributed to mediocre results at the box office; it earned back its budget and marketing, but RKO lost any chance of a major profit. The fact that Citizen Kane ignored many Hollywood conventions meant that the film confused and angered the 1940s cinema public. Exhibitor response was scathing; most theater owners complained bitterly about the adverse audience reaction and the many walkouts. Only a few saw fit to acknowledge Welles’s artistic technique. RKO shelved the film and did not re-release it until 1956.

During the 1950s, the film came to be seen by young French film critics such as François Truffaut as exemplifying the “auteur theory“, in which the director is the “author” of a film. Truffaut, Godard and others inspired by Welles’s example made their own films, giving birth to the Nouvelle Vague. In the 1960s Citizen Kane became popular on college campuses as a film-study exercise and as an entertainment subject. Its revivals on television, home video and DVD have enhanced its “classic” status and ultimately recouped costs. The film is considered by most film critics and historians to be one of, if not the, greatest motion pictures in cinema history.

The Magnificent Ambersons

Welles’s second film for RKO was The Magnificent Ambersons, adapted from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Booth Tarkington. George Schaefer hoped to make money with this film, since he lost money with Citizen Kane. Ambersons had been adapted for The Campbell Playhouse by Welles, for radio, and Welles then wrote the screen adaptation. Toland was not available, so Stanley Cortez was named cinematographer. The meticulous Cortez worked slowly and the film lagged behind schedule and over budget. Prior to production, Welles’s contract was renegotiated, revoking his right to control the final cut.

Journey into Fear

At RKO’s request, Welles worked on an adaptation of Eric Ambler‘s spy thriller, Journey into Fear, co-written with Joseph Cotten. In addition to acting in the film, Welles was the producer. Direction was credited to Norman Foster. Welles later said that they were in such a rush that the director of each scene was determined by whoever was closest to the camera.

CBS then offered Welles a radio series called the Orson Welles Show. It was a half-hour variety show of short stories, comedy skits, poetry and musical numbers. Joining the original Mercury Theatre cast was Cliff Edwards, the voice of Jiminy Cricket, “on loan from Walt Disney“. The variety format was unpopular with listeners and Welles soon was forced to limit the content of the show to telling one half-hour story for each episode.

War work

It’s All True

To complicate matters during the production of Ambersons and Journey into Fear, Welles was approached by Nelson Rockefeller and Jock Whitney to produce a documentary film about South America. This was at the behest of the federal government’s Good Neighbor policy, a wartime propaganda effort designed to prevent Latin America from allying with the Axis powers. Welles saw his involvement as a national service, since his physical condition excused him from military service.

Expected to film the Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Welles rushed to finish the editing on Ambersons and his acting scenes in Journey into Fear. Ending his CBS radio show, he lashed together a rough cut of Ambersons with Robert Wise, who edited Citizen Kane, and left for Brazil. Wise was to join him in Rio to complete the film, but never arrived. A provisional final cut arranged via phone call, telegram and shortwave radio was previewed without Welles’s approval in Pomona, in a double bill, to a mostly negative audience response, particularly to the character of Aunt Fanny played by Agnes Moorehead. Whereas Schaefer argued that Welles be allowed to complete his version of the film, and that an archival copy be kept with the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, RKO disagreed. With Welles in South America, there was no practical means of his editing the film.

As a result of difficult financial circumstances at RKO in 1940–42, major changes occurred at the studio in 1942[43] Floyd Odlum took control of RKO and began changing its direction. Rockefeller, the most significant backer of the Brazil project, left the RKO board of directors. Around that time, the principal sponsor of Welles at RKO, studio president George Schaefer, resigned. The changes throughout RKO caused reevaluations of projects. RKO took control of Ambersons, formed a committee, which was ordered to edit the film into what the studio considered a commercial format. They removed fifty minutes of Welles’s footage, re-shot sequences, rearranged the scene order, and added a happy ending. Koerner released the shortened film on the bottom of a double-bill with the Lupe Vélez comedy, Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost. Ambersons was an expensive flop for RKO, although it received four Academy Award nominations including Best Picture and Best Supporting Actress for Agnes Moorehead.

Welles’s South American documentary, entitled It’s All True, budgeted at one million dollars with half of its budget coming from the U.S. Government upon completion, grew in ambition and budget while Welles was in South America. While the film originally was to be a documentary on Carnaval, Welles added a new story, which recreated the journey of the jangadeiros, four poor fishermen who made a 1,500-mile (2,400 km) journey on their open raft to petition Brazilian President Vargas about their working conditions. The four had become national folk heroes; Welles first read of their journey in TIME. Their leader, Jacare, died in a filming mishap. RKO, in limited contact with Welles, attempted to rein in the production. Most of the crew and budget were withdrawn from the film. In addition, the Mercury staff was removed from the studio in the U.S.

Welles requested resources to finish the film. He was given a limited amount of black-and-white film stock and a silent camera. He completed the sequence, but RKO refused to support further production on the film. Surviving footage was released in 1993, including a rough reconstruction of the “Four Men on a Raft” segment. Meanwhile, RKO asserted in public that Welles had gone to Brazil without a screenplay and had squandered a million dollars. Their official company slogan for the next year was, “Showmanship in place of Genius” – which was taken as a slight against Welles.

On returning to Hollywood, Welles next worked on radio. CBS offered him two weekly series, Hello Americans, based on the research he had done in Brazil, and Ceiling Unlimited, sponsored by Lockheed, a wartime salute to advances in aviation. Both featured several members of his original Mercury Theatre troupe. Within months, Hello Americans was canceled and Welles was replaced as host of Ceiling Unlimited by Joseph Cotten. Welles guest-starred on a variety of shows, notably guest-hosting Jack Benny shows for a month in 1943. He took an increasingly active role in American and international politics and used journalism to communicate his forceful ideas widely.

In 1943, Welles married Rita Hayworth. They had one child, Rebecca Welles, and divorced five years later in 1948. In between, Welles found work as an actor in other films. He starred in the 1944 film adaptation of Jane Eyre, trading credit as associate producer for top billing over Joan Fontaine.

He had a cameo in the 1944 wartime salute Follow the Boys, in which he performed his Mercury Wonder Show magic act and “sawed” Marlene Dietrich in half after Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn refused to allow Hayworth to perform.

In 1944, Welles was offered a new radio show, broadcast on the Columbia Pacific Network, The Orson Welles Almanac. It was a half-hour variety show, with Mobil Oil as sponsor. After the success of his stand-in hosting on The Jack Benny Show, the focus was primarily on comedy. His hosting on the Jack Benny show included self-deprecating jokes and story lines about his being a “genius” and overriding ideas advanced by other cast members. The trade papers were not eager to accept Welles as a comedian, and Welles complained on-air about the poor quality of the scripts. When Welles started his Mercury Wonder Show a few months later, traveling to armed forces camps and performing magic tricks and comedy, the radio show was broadcast live from the camps and the material took on a decidedly wartime flavor.

While he found no studio willing to hire him as a director, Welles’s popularity as an actor continued. Cresta Blanca Wines gave Welles its radio series This Is My Best to direct, but after a month he was fired for creative differences. He started writing a political column for the New York Post, called Orson Welles’s Almanac. While the paper wanted Welles to write about Hollywood gossip, Welles explored serious political issues. His activism for world peace took considerable amounts of his time. The Post column eventually failed in syndication because of contradictory expectations and was dropped by the Post.

Post-war work

The Stranger

Director and star Orson Welles at work on

The Stranger (October 1945)

In 1946, International Pictures released Welles’s film The Stranger, starring Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young and Welles. Sam Spiegel produced the film, which follows the hunt for a Nazi war criminal living under an alias in the United States. While Anthony Veiller was credited with the screenplay, it was rewritten by Welles and John Huston. Disputes occurred during editing between Spiegel and Welles. The film was a box office success and it helped his standing with the studios.

Around the World

In the summer of 1946, Welles directed Around the World, a musical stage adaptation of the Jules Verne novel Around the World in Eighty Days with the book by Welles and music by Cole Porter. Producer Mike Todd, who would later produce the successful 1956 film adaptation, pulled out from the lavish and expensive Broadway production, leaving Welles to support the finances. When Welles ran out of money he convinced Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn to send enough money to continue the show, and in exchange Welles promised to write, produce, direct and star in a film for Cohn for no further fee. The stage show soon failed due to poor box-office, with Welles unable to claim the losses on his taxes. The complex financial arrangements — concerning the show, its losses, and Welles’s arrangement with Cohn — resulted in a tax dispute between Welles and the IRS.

Radio series

In 1946, Welles began two new radio series — The Mercury Summer Theatre on the Air for CBS, and Orson Welles Commentaries for ABC. While Mercury Summer Theatre featured half-hour adaptations of some classic Mercury radio shows from the 1930s, the first episode was a condensation of his Around the World stage play, and is the only record of Cole Porter’s music for the project. Several original Mercury actors returned for the series, as well as Bernard Herrmann. It was only scheduled for the summer months, and Welles invested his earnings into his failing stage play. Commentaries was a political vehicle for him, continuing the themes from his New York Post column. Again, Welles lacked a clear focus, until the NAACP brought to his attention the case of Isaac Woodard. Welles brought significant attention to Woodard’s cause. Soon Welles was hanged in effigy in the South and theaters refused to show The Stranger in several southern states.

The Lady from Shanghai

The film that Welles was obliged to make in exchange for Harry Cohn’s help in financing the stage production Around the World was The Lady from Shanghai, filmed in 1947 for Columbia Pictures. Intended as a modest thriller, the budget skyrocketed after Cohn suggested that Welles’s then-estranged second wife Rita Hayworth co-star.

Cohn disliked Welles’s rough-cut, particularly the confusing plot and lack of close-ups, and was not in sympathy with Welles’s Brechtian use of irony and black comedy, especially in a farcical courtroom scene. Cohn ordered extensive editing and re-shoots. After heavy editing by the studio, approximately one hour of Welles’s first cut was removed, including much of a climactic confrontation scene in an amusement park funhouse. While expressing displeasure at the cuts, Welles was appalled particularly with the musical score. The film was considered a disaster in America at the time of release, though the closing shootout in a hall of mirrors has since become a touchstone of film noir. Not long after release, Welles and Hayworth finalized their divorce.

Although The Lady From Shanghai was acclaimed in Europe, it was not embraced in the U.S. until decades later. Influential modern critics including David Kehr declared it a masterpiece, with Kehr calling it “the weirdest great movie ever made.” A similar difference in reception on opposite sides of the Atlantic followed by greater American acceptance befell the Welles-inspired Chaplin film Monsieur Verdoux, originally to be directed by Welles starring Chaplin, then directed by Chaplin with the idea credited to Welles.

Macbeth

Prior to 1948, Welles convinced Republic Pictures to let him direct a low-budget version of Macbeth, which featured highly stylized sets and costumes, and a cast of actors lip-syncing to a pre-recorded soundtrack, one of many innovative cost-cutting techniques Welles deployed in an attempt to make an epic film from B-movie resources. The script, adapted by Welles, is a violent reworking of Shakespeare’s original, freely cutting and pasting lines into new contexts via a collage technique and recasting Macbeth as a clash of pagan and proto-Christian ideologies. Some voodoo trappings of the famous Welles/Houseman Negro Theatre stage adaptation are visible, especially in the film’s characterization of the Weird Sisters, who create an effigy of Macbeth as a charm to enchant him. Of all Welles’s post-Kane Hollywood productions, Macbeth is stylistically closest to Citizen Kane in its long takes and deep focus photography. Shots of the increasingly isolated Scottish king looming in the foreground while characters address him from deep in the background overtly reference Kane.

Republic initially trumpeted the film as an important work but decided it did not care for the Scottish accents and held up general release for almost a year after early negative press reaction, including Life ‘s comment that Welles’s film “doth foully slaughter Shakespeare.”[44] Welles left for Europe, while co-producer and lifelong supporter Richard Wilson reworked the soundtrack. Welles returned and cut twenty minutes from the film at Republic’s request and recorded narration to cover some gaps. The film was decried as a disaster. Macbeth had influential fans in Europe, especially the French poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, who hailed the film’s “crude, irreverent power” and careful shot design, and described the characters as haunting “the corridors of some dreamlike subway, an abandoned coal mine, and ruined cellars oozing with water.”[45]

In the late 1970s, a fully restored version of Macbeth was released that followed Welles’s original vision, and all prints of the truncated theatrical release have gradually been withdrawn from circulation, turning Welles’s compulsory recut version—which has the distinction of being created by the director himself—into something of a lost work.

Europe (1948–1956)

Welles left Hollywood for Europe in late 1947, enigmatically saying that he had chosen “freedom.” In Italy he starred as Cagliostro in the 1948 film Black Magic. His co-star, Akim Tamiroff, impressed Welles so much that Tamiroff would appear in four of Welles’s productions during the 1950s and 1960s.

The Third Man

The following year, Welles starred as Harry Lime in Carol Reed‘s The Third Man, alongside Joseph Cotten, his friend and co-star from Citizen Kane, with a script by Graham Greene and a memorable score by Anton Karas. The film was an international smash hit, but unfortunately for Welles, he turned down a percentage of the gross in exchange for a lump-sum advance.

The film is also memorable for a scene that has entered Hollywood lore, an unscripted monologue Welles inserted that took director Reed completely by surprise. Talking to Joseph Cotton in a carriage atop a Ferris wheel, Lime says: “Don’t be so gloomy. After all it’s not that awful. Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

A few years later, British radio producer Harry Alan Towers would resurrect the Lime character in the radio series The Lives of Harry Lime. The 1951 series included new recordings by Karas and was very successful, running for 52 weeks. Welles claimed to have written a handful of episodes—a claim disputed by Towers, who maintains that they were written by Ernest Borneman—which later served as the basis for the screenplay by Welles, Mr. Arkadin (1955).

Welles appeared as Cesare Borgia in the 1949 Italian film Prince of Foxes, with Tyrone Power and Mercury Theatre alumnus Everett Sloane, and as the Mongol warrior Bayan in the 1950 film version of the novel The Black Rose (again with Tyrone Power). [46]

Othello

During this time, Welles was channeling his money from acting jobs into a self-financed film version of Shakespeare’s play Othello. From 1949 to 1951, Welles worked on Othello, filming on location in Europe and Morocco. The film featured Welles’s friends, Micheál Mac Liammóir as Iago and Hilton Edwards as Desdemona‘s father Brabantio. Suzanne Cloutier starred as Desdemona and Campbell Playhouse alumnus Robert Coote appeared as Iago’s associate Roderigo.

Filming was suspended several times as Welles ran out of funds and left for acting jobs, accounted in detail in MacLiammóir’s published memoir Put Money in Thy Purse. When it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival it won the Palme d’Or, but the film did not receive a general release in the United States until 1955 (by which time Welles had re-cut the first reel and re-dubbed most of the film, removing Cloutier’s voice entirely), and it played only in New York and Los Angeles. The American release prints had a technically flawed soundtrack, suffering from a drop-out of sound at every quiet moment. Welles’s daughter, Beatrice Welles-Smith, restored Othello in 1992 for a wide re-release. The restoration included reconstructing Angelo Francesco Lavagnino‘s original musical score, which was originally inaudible, and adding ambient stereo sound effects, which were not in the original film. The restoration went on to a successful theatrical run in America. A print of the U.S. version was released on laserdisc in 1995 but soon withdrawn after a legal challenge by Beatrice Welles-Smith. The original Cannes version has survived but is not available commercially.

In 1952, Welles continued finding work in England after the success of the Harry Lime radio show. Harry Alan Towers offered Welles another series, The Black Museum, which ran for 52 weeks with Welles as host and narrator. Director Herbert Wilcox offered Welles the part of the murdered victim in Trent’s Last Case, based on the novel by E. C. Bentley. In 1953, the BBC hired Welles to read an hour of selections from Walt Whitman‘s epic poem Song of Myself. Towers hired Welles again, to play Professor Moriarty in the radio series, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, starring John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson.

Welles briefly returned to America to make his first appearance on television, starring in the Omnibus presentation of King Lear, broadcast live on CBS October 18, 1953. Directed by Peter Brook, the production costarred Natasha Parry, Beatrice Straight and Arnold Moss.[47] While Welles received good notices, he was guarded by IRS agents, prohibited to leave his hotel room when not at the studio, prevented from making any purchases, and forced to turn over the entire sum (less expenses) he earned, all of which went to his tax bill.

In 1954, director George More O’Ferrall offered Welles the title role in the ‘Lord Mountdrago’ segment of Three Cases of Murder, co-starring Alan Badel. Herbert Wilcox cast Welles as the antagonist in Trouble in the Glen opposite Margaret Lockwood, Forrest Tucker and Victor McLaglen. Old friend John Huston cast him as Father Mapple in his 1956 film adaptation of Herman Melville‘s Moby-Dick, starring Gregory Peck.

Mr. Arkadin

Welles in Madrid during the filming of Mr. Arkadin in 1954

Welles’s next turn as director was the film Mr. Arkadin (1955), which was produced by his political mentor from the 1940s, Louis Dolivet. It was filmed in France, Germany, Spain and Italy on a very limited budget. Based loosely on several episodes of the Harry Lime radio show, it stars Welles as a billionaire who hires a man to delve into the secrets of his past. The film stars Robert Arden, who had worked on the Harry Lime series; Welles’s third wife, Paola Mori, whose voice was dubbed by actress Billie Whitelaw; and guest stars Akim Tamiroff, Michael Redgrave, Katina Paxinou and Mischa Auer. Frustrated by his slow progress in the editing room, producer Dolivet removed Welles from the project and finished the film without him. Eventually five different versions of the film would be released, two in Spanish and three in English. The version that Dolivet completed was retitled Confidential Report. In 2005 Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum oversaw a reconstruction of the surviving film elements. Included in a DVD box set (The Complete Mr. Arkadin) released by The Criterion Collection, it is considered by Welles scholar and director Peter Bogdanovich to be the best version of Welles’s original intentions for the film.

In 1955, Welles also directed two television series for the BBC. The first was Orson Welles’ Sketch Book, a series of six 15-minute shows featuring Welles drawing in a sketchbook to illustrate his reminiscences for the camera (including such topics as the filming of It’s All True and the Isaac Woodard case), and the second was Around the World with Orson Welles, a series of six travelogues set in different locations around Europe (such as Venice, the Basque Country between France and Spain, and England). Welles served as host and interviewer, his commentary including documentary facts and his own personal observations (a technique he would continue to explore in later works). A seventh episode of this series, based on the Gaston Dominici case, was suppressed at the time by the French government, but was reconstructed after Welles’s death and released to video in 1999.

In 1956, Welles completed Portrait of Gina. Dissatisfied with the results—Welles recalled he had worked on it a lot and the result looked like it—he left the only print behind at the Ritz Hotel in Paris.} The film cans would remain in a lost-and-found locker at the hotel for several decades, where they were discovered after Welles’s death. The work posthumously aired on German television under the title Viva Italia, a 30-minute personal essay on Gina Lollobrigida and the general subject of Italian sex symbols.

Return to Hollywood (1956–1959)

Welles the magician with Lucille Ball in

I Love Lucy (October 15, 1956)

In 1956, Welles returned to Hollywood, guesting on radio shows, notably as narrator of Tomorrow, a nuclear holocaust drama produced by the Federal Civil Defense Administration. He guest starred on television shows including I Love Lucy, and began filming a projected pilot for Desilu, owned by Lucille Ball and her husband Desi Arnaz, who had recently purchased the former RKO studios. The film was The Fountain of Youth, based on a story by John Collier. Originally deemed not viable as a pilot, the film was not aired until 1958 — and won the Peabody Award for excellence. Welles’s next feature film role was in Man in the Shadow for Universal Pictures in 1957, starring Jeff Chandler. Around this time period Welles began to suffer from weight problems that would eventually cause a deterioration in his health.

Touch of Evil

Welles as corrupt police captain Hank Quinlan in

Touch of Evil (1958)

Welles stayed on at Universal to direct (and co-star with) Charlton Heston in the 1958 film Touch of Evil, based on Whit Masterson‘s novel Badge of Evil. Welles, who wrote the screenplay for the film, claimed never to have read the book. Originally only hired as an actor, Welles was promoted to director by Universal Studios at the insistence of Charlton Heston.[48]:154 The film reunited many actors and technicians with whom Welles had worked in Hollywood in the 1940s, including cameraman Russell Metty (The Stranger), makeup artist Maurice Seiderman (Citizen Kane), and actors Joseph Cotten, Marlene Dietrich and Akim Tamiroff). Filming proceeded smoothly, with Welles finishing on schedule and on budget, and the studio bosses praising the daily rushes. Nevertheless, after the end of production, the studio re-edited the film, re-shot scenes, and shot new exposition scenes to clarify the plot.[48]:175–176 Welles wrote a 58-page memo outlining suggestions and objections, stating that the film was no longer his version—it was the studio’s, but as such, he was still prepared to help with it.[48]:175–176 The studio followed a few of the ideas, but cut another 30 minutes from the film and released it. The film was widely praised across Europe, and was awarded the top prize at the Brussels World’s Fair.

In 1978, a longer preview version of the film was discovered and released. In 1998, editor Walter Murch and producer Rick Schmidlin, consulting Welles’s memo, used a workprint version to attempt to create a version of the film as close as possible to that outlined by Welles in the memo.

As Universal reworked Touch of Evil, Welles began filming his adaptation of Miguel de Cervantes‘ novel Don Quixote in Mexico, starring Mischa Auer as Quixote and Akim Tamiroff as Sancho Panza. While filming would continue in fits and starts for several years, Welles would never complete the project.

Welles continued acting, notably in The Long, Hot Summer (1958) and Compulsion (1959), but soon returned to Europe.

Return to Europe (1959–1970)

He continued shooting Don Quixote in Spain and Italy, but replaced Mischa Auer with Francisco Reiguera, and resumed acting jobs. In Italy in 1959, Welles directed his own scenes as King Saul in Richard Pottier’s film David and Goliath. In Hong Kong he co-starred with Curt Jürgens in Lewis Gilbert‘s film Ferry to Hong Kong. In 1960, in Paris he co-starred in Richard Fleischer‘s film Crack in the Mirror. In Yugoslavia he starred in Richard Thorpe‘s film The Tartars and Veljko Bulajić‘s “Battle of Neretva“.

Throughout the 1960s, filming continued on Quixote on-and-off until the decade, as Welles evolved the concept, tone and ending several times. Although he had a complete version of the film shot and edited at least once, he would continue toying with the editing well into the 1980s, he never completed a version film he was fully satisfied with, and would junk existing footage and shoot new footage. (In one case, he had a complete cut ready in which Quixote and Sancho Panza end up going to the moon, but he felt the ending was rendered obsolete by the 1969 moon landings, and burned 10 reels of this version.) As the process went on, Welles gradually voiced all of the characters himself and provided narration. In 1992, the director Jesús Franco constructed a film out of the portions of Quixote left behind by Welles. Some of the film stock had decayed badly. While the Welles footage was greeted with interest, the post-production by Franco was met with harsh criticism.

Welles being interviewed in 1960

In 1961, Welles directed In the Land of Don Quixote, a series of eight half-hour episodes for the Italian television network RAI. Similar to the Around the World with Orson Welles series, they presented travelogues of Spain and included Welles’s wife, Paola, and their daughter, Beatrice. Though Welles was fluent in Italian, the network was not interested in him providing Italian narration because of his accent, and the series sat unreleased until 1964, by which time the network had added Italian narration of its own. Ultimately, versions of the episodes were released with the original musical score Welles had approved, but without the narration.

The Trial

In 1962, Welles directed his adaptation of The Trial, based on the novel by Franz Kafka and produced by Alexander Salkind and Michael Salkind. The cast included Anthony Perkins as Josef K, Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Paola Mori and Akim Tamiroff. While filming exteriors in Zagreb, Welles was informed that the Salkinds had run out of money, meaning that there could be no set construction. No stranger to shooting on found locations, Welles soon filmed the interiors in the Gare d’Orsay, at that time an abandoned railway station in Paris. Welles thought the location possessed a “Jules Verne modernism” and a melancholy sense of “waiting”, both suitable for Kafka. The film failed at the box-office. Peter Bogdanovich would later observe that Welles found the film riotously funny. During the filming, Welles met Oja Kodar, who would later become his muse, star and mistress for the last twenty years of his life. Welles also stated in an interview with the BBC that it was his best film.[49]

Welles played a film director in La Ricotta (1963)—Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s segment of the Ro.Go.Pa.G. movie, although his renowned voice was dubbed by Italian writer Giorgio Bassani.[13]:516 He continued taking what work he could find acting, narrating or hosting other people’s work, and began filming Chimes at Midnight, which was completed in 1966. Filmed in Spain, it was a condensation of five Shakespeare plays, telling the story of Falstaff and his relationship with Prince Hal. The cast included Keith Baxter, John Gielgud, Jeanne Moreau, Fernando Rey and Margaret Rutherford, with narration by Ralph Richardson. Music was again by Angelo Francesco Lavagnino. Jess Franco served as second unit director.

Chimes at Midnight

Welles during the production of the stage version of Chimes at Midnight in 1960

Chimes at Midnight was based on Welles’s play Five Kings which condensed five of Shakespeare’s plays into one show in order to focus on the story of Falstaff. Welles produced the show in New York in 1939 but the opening night, where part 1 was acted, was a disaster and part 2 was never put on. He revamped the show and revisited it in 1960 at the Gate Theatre in Dublin. But again, it was not successful. However, this later production was used as the base for the movie. The script contained text from five plays: primarily Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry IV, Part 2, but also Richard II, Henry V and The Merry Wives of Windsor. Keith Baxter played Prince Hal, and internationally respected Shakespearean interpreter, John Gielgud, played the King, Henry IV. The film’s narration, spoken by Ralph Richardson, is taken from the chronicler Raphael Holinshed. According to Jeanne Moreau, Welles delayed filming for two weeks due to stage fright. Welles held this film in high regard and considered it, along with The Trial, his best work. As he remarked in 1982, “If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, that’s the one I’d offer up.”[50]

In 1966, Welles directed a film for French television, an adaptation of The Immortal Story, by Karen Blixen. Released in 1968, it stars Jeanne Moreau, Roger Coggio and Norman Eshley. The film had a successful run in French theaters. At this time Welles met Oja Kodar again, and gave her a letter he had written to her and had been keeping for four years; they would not be parted again. They immediately began a collaboration both personal and professional. The first of these was an adaptation of Blixen’s The Heroine, meant to be a companion piece to The Immortal Story and starring Kodar. Unfortunately, funding disappeared after one day’s shooting. After completing this film, he appeared in a brief cameo as Cardinal Wolsey in Fred Zinnemann‘s adaptation of A Man for All Seasons—a role for which he won considerable acclaim.

In 1967, Welles began directing The Deep, based on the novel Dead Calm by Charles Williams and filmed off the shore of Yugoslavia. The cast included Jeanne Moreau, Laurence Harvey and Kodar. Personally financed by Welles and Kodar, they could not obtain the funds to complete the project, and it was abandoned a few years later after the death of Harvey. The surviving footage was eventually edited and released by the Filmmuseum München. In 1968 Welles began filming a TV special for CBS under the title Orson’s Bag, combining travelogue, comedy skits and a condensation of Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice with Welles as Shylock. Funding for the show sent by CBS to Welles in Switzerland was seized by the IRS. Without funding, the show was not completed. The surviving film clips portions were eventually released by the Filmmuseum München.

In 1969, Welles authorized the use of his name for a cinema in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Orson Welles Cinema remained in operation until 1986, with Welles making a personal appearance there in 1977. Also in 1969 he played a supporting role in John Huston‘s The Kremlin Letter. Drawn by the numerous offers he received to work in television and films, and upset by a tabloid scandal reporting his affair with Kodar, Welles abandoned the editing of Don Quixote and moved back to America in 1970.

Later career (1970–1985)

Welles returned to Hollywood, where he continued to self-finance his film and television projects. While offers to act, narrate and host continued, Welles also found himself in great demand on television talk shows. He made frequent appearances for Dick Cavett, Johnny Carson, Dean Martin and Merv Griffin.

Welles’s primary focus during his final years was The Other Side of the Wind, an unfinished project that was filmed intermittently between 1970 and 1976. Written by Welles, it is the story of an aging film director (John Huston) looking for funds to complete his final film. The cast includes Peter Bogdanovich, Susan Strasberg, Norman Foster, Edmond O’Brien, Cameron Mitchell and Dennis Hopper. Financed by Iranian backers, ownership of the film fell into a legal quagmire after the Shah of Iran was deposed. While there have been several reports of all the legal disputes concerning ownership of the film being settled, enough disputes still exist to prevent its release.

Welles portrayed Louis XVIII of France in the 1970 film Waterloo, and narrated the beginning and ending scenes of the historical comedy Start the Revolution Without Me (1970).

In 1971, Welles directed a short adaptation of Moby-Dick, a one-man performance on a bare stage, reminiscent of his 1955 stage production Moby Dick—Rehearsed. Never completed, it was eventually released by the Filmmuseum München. He also appeared in Ten Days’ Wonder, co-starring with Anthony Perkins and directed by Claude Chabrol, based on a detective novel by Ellery Queen. That same year, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences gave him an honorary award “For superlative artistry and versatility in the creation of motion pictures”. Welles pretended to be out of town and sent John Huston to claim the award, thanking the Academy on film. Huston criticized the Academy for awarding Welles, even while they refused to give Welles any work.

In 1972, Welles acted as on-screen narrator for the film documentary version of Alvin Toffler‘s 1970 book Future Shock. Working again for a British producer, Welles played Long John Silver in director John Hough‘s Treasure Island (1972), an adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson novel, which had been the second story broadcast by The Mercury Theatre on the Air in 1938. This was the last time he played the lead role in a major film. Welles also contributed to the script, his writing credit was attributed to the pseudonym ‘O. W. Jeeves’. Some of Welles’ original recorded dialog was redubbed by Robert Rietty.

In 1973, Welles completed F for Fake, a personal essay film about art forger Elmyr de Hory and the biographer Clifford Irving. Based on an existing documentary by François Reichenbach, it included new material with Oja Kodar, Joseph Cotten, Paul Stewart and William Alland. An excerpt of Welles’s 1930s War of the Worlds broadcast was recreated for this film; however, none of the dialogue heard in the film actually matches what was originally broadcast. Welles filmed a five-minute trailer, rejected in the U.S., that featured several shots of a topless Kodar.

Welles hosted and narrated a syndicated anthology series, Orson Welles’s Great Mysteries, over the 1973–1974 television season. It did not last beyond that season; however, the program could be perceived as a television revival of the Mercury Theatre whose executive producer Welles had been in the 1930s and 1940s. The year 1974 also saw Welles lending his voice for that year’s remake of Agatha Christie‘s classic thriller Ten Little Indians produced by his former associate, Harry Alan Towers and starring an international cast that included Oliver Reed, Elke Sommer and Herbert Lom.

In 1975, Welles narrated the documentary Bugs Bunny: Superstar, focusing on Warner Bros. cartoons from the 1940s. Also in 1975, the American Film Institute presented Welles with its third Lifetime Achievement Award (the first two going to director John Ford and actor James Cagney). At the ceremony, Welles screened two scenes from the nearly finished The Other Side of the Wind.

In 1976, Paramount Television purchased the rights for the entire set of Rex Stout‘s Nero Wolfe stories for Orson Welles.[51][52] Welles had once wanted to make a series of Nero Wolfe movies, but Rex Stout – who was leery of Hollywood adaptations during his lifetime after two disappointing 1930s films – turned him down.[53] Paramount planned to begin with an ABC-TV movie and hoped to persuade Welles to continue the role in a mini-series.[54] Frank D. Gilroy was signed to write the television script and direct the TV movie on the assurance that Welles would star, but by April 1977 Welles had bowed out.[55] In 1980 the Associated Press reported “the distinct possibility” that Welles would star in a Nero Wolfe TV series for NBC television.[56] Again, Welles bowed out of the project due to creative differences and William Conrad was cast in the role.[57]

In 1979, Welles completed his documentary Filming Othello, which featured Michael MacLiammoir and Hilton Edwards. Made for West German television, it was also released in theaters. That same year, Welles completed his self-produced pilot for The Orson Welles Show television series, featuring interviews with Burt Reynolds, Jim Henson and Frank Oz and guest-starring The Muppets and Angie Dickinson. Unable to find network interest, the pilot was never broadcast. Also in 1979, Welles appeared in the biopic The Secret of Nikola Tesla, and a cameo in The Muppet Movie as Lew Lord.

Beginning in the late 1970s, Welles participated in a series of famous television commercial advertisements. For two years he was on-camera spokesman for the Paul Masson Vineyards,[58] and sales grew by one third during the time Welles intoned what became a popular catchphrase: “We will sell no wine before its time.”[59] He was also the voice behind the long-running Carlsberg “Probably the best lager in the world” campaign,[60] promoted Domecq sherry on British television[61] and provided narration on adverts for Findus, though the actual adverts have been overshadowed by a famous blooper reel of voice recordings, known as the Frozen Peas reel.

In 1981, Welles hosted the documentary The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, about Renaissance-era prophet Nostradamus. In 1982, the BBC broadcast The Orson Welles Story in the Arena series. Interviewed by Leslie Megahey, Welles examined his past in great detail, and several people from his professional past were interviewed as well. It was reissued in 1990 as With Orson Welles: Stories of a Life in Film. Welles provided narration for the tracks “Defender” from Manowar‘s album Fighting the World and “Dark Avenger” on Manowar‘s 1982 album, Battle Hymns. His name was misspelled on the latter album, as he was credited as “Orson Wells”.[62]

During the 1980s, Welles worked on such film projects as The Dreamers, based on two stories by Isak Dinesen and starring Oja Kodar, and Orson Welles’ Magic Show, which reused material from his failed TV pilot. Another project he worked on was Filming The Trial, the second in a proposed series of documentaries examining his feature films. While much was shot for these projects, none of them was completed. All of them were eventually released by the Filmmuseum München.

In 1984, Welles narrated the short-lived television series Scene of the Crime. During the early years of Magnum, P.I., Welles was the voice of the unseen character Robin Masters, a famous writer and playboy. Welles’s death forced this minor character to largely be written out of the series. In an oblique homage to Welles, the Magnum, P.I. producers ambiguously concluded that story arc by having one character accuse another of having hired an actor to portray Robin Masters.[63] He also, in this penultimate year released a music single, titled “I Know What It Is To Be Young (But You Don’t Know What It Is To Be Old)”, which he recorded under Italian label Compagnia Generale del Disco. The song was performed with the Nick Perito Orchestra and the Ray Charles Singers and produced by Jerry Abbott who was father to famed metal guitarist Dimebag Darrell.[64]

The last film roles before Welles’s death included voice work in the animated films The Enchanted Journey (1984) and The Transformers: The Movie (1986), in which he played the planet-eating robot Unicron. His last film appearance was in Henry Jaglom‘s 1987 independent film Someone to Love, released after his death but produced before his voice-over in Transformers: The Movie. His last television appearance was on the television show Moonlighting. He recorded an introduction to an episode entitled “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice”, which was partially filmed in black and white. The episode aired five days after his death and was dedicated to his memory.

In the mid-1980s, Henry Jaglom taped lunch conversations with Welles at Los Angeles’s Ma Maison as well as in New York. Edited transcripts of these sessions appear in Peter Biskind‘s 2013 book My Lunches With Orson: Conversations Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles.[65]

Personal life

Relationships and family

Orson Welles and Chicago-born actress and socialite Virginia Nicolson (1916–1996) were married November 14, 1934.[13]:332 The couple divorced February 1, 1940.[66][67]

Welles fell in love with Mexican actress Dolores del Río, ten years his senior, with whom he was involved between 1938 and 1942.[68] They acted together in the movie Journey into Fear (1943) but the affair ended soon after filming ended. Rebecca Welles, the daughter of Welles and Hayworth, met Del Rio in 1954 and said, “My father considered her the great love of his life … She was a living legend in the history of my family”.[69]

Welles married Rita Hayworth in 1943. The couple became estranged by 1946 – Welles blamed Hayworth for making unfounded accusations of infidelity, and after he was turned out of the marital bed he then actually started to have affairs, which in turn prompted Hayworth to have affairs of her own. They briefly reconciled in 1947 during the making of The Lady from Shanghai, before finally separating. In 1948 Hayworth filed for divorce, her reason to the press being, “I can’t take his genius any more.”[70] During his last interview and only five hours before his death, Welles answered Merv Griffin‘s suggestive comment “But one of your wives—oh, I have envied you so many years for Rita Hayworth”, by calling her “one of the dearest and sweetest women that ever lived” and saying that he was “lucky enough to have been with her longer than any of the other men in her life.”[71]

In 1955, Welles married actress Paola Mori (née Countess Paola di Girifalco), an Italian aristocrat who starred as Raina Arkadin in his 1955 film, Mr. Arkadin. The couple had embarked on a passionate affair, and after she became pregnant they were married at her parents’ insistence.[17]:168 They were wed in London May 8, 1955,[13]:417, 419 and never divorced.

Croatian-born actress Oja Kodar became Welles’s longtime companion both personally and professionally from 1966 onwards, and they lived together for some of the last 19 years of his life. They first met in Zagreb in 1962, while Welles was filming The Trial, and embarked on a passionate, short-lived affair which ended when Paola Mori had a cancer scare and Welles returned to his wife. Kodar assumed Welles had left for good, and Welles hired a private detective to track down Kodar, to no avail. Three years passed, and Kodar was by then living in Paris and in a relationship with a struggling young actor. When they saw a press feature that Welles was in Paris, the young actor persuaded a reluctant Kodar to use her influence with Welles to get him a job. When she telephoned him, Welles immediately rushed to her hotel room, broke down the door, and pulled out a small metal box from his jacket. It contained a love letter to her. He had been carrying it every day for the last three years, in case he might meet her again one day.

With the passing years, Welles’s domestic arrangements became more complicated. From 1966 he always maintained at least two separate homes, one with Kodar, the other with Mori and their daughter Beatrice. In the 1960s and 1970s, he shared houses just outside Paris and Madrid with Kodar. Although British tabloids reported his affair with Kodar as early as 1969 (which was a factor in his moving permanently to the United States in 1970), both Mori and Beatrice remained oblivious as to Kodar’s existence until 1984. Welles set up a home with Mori and Beatrice in the United States (first in Sedona, then in Las Vegas), ostensibly because the climate would be good for his asthma. But while they lived in Las Vegas, he spent most of his time in Los Angeles, where he openly shared a house with Kodar. When Mori found out about Kodar in 1984, she threw him out of their Las Vegas house, and she and Beatrice did not see him for the last year of his life, although they still talked regularly on the telephone.

This situation had serious ramifications for the copyright status of his work after his death. Welles left Kodar his Los Angeles home and the rights to his unfinished films, and turned the rest over to Mori. Mori contended that she should have been left everything, and a year after Welles’s death, Mori and Kodar finally agreed on the settlement of his will. On the way to their meeting to sign the papers, however, Mori was killed in a car accident in August 1986. Mori’s half of the estate was inherited by Beatrice, who refused to come to an arrangement with Kodar, who she blames for undermining her parents’ marriage. Legal wranglings between the two have persisted for over 25 years, leading to complex ongoing legal battles over who owns his unfinished films.

Welles had three daughters from his marriages: Christopher Welles Feder (born March 27, 1938, with Virginia Nicolson); Rebecca Welles Manning (December 17, 1944 – October 14, 2004,[72] with Rita Hayworth); and Beatrice Welles (born November 13, 1955, with Paola Mori). His only known son, British director Michael Lindsay-Hogg (Sir Michael Lindsay-Hogg, 5th baronet, born May 5, 1940), is from Welles’s affair with Irish actress Geraldine Fitzgerald, then the wife of Sir Edward Lindsay-Hogg, 4th baronet. Although Hogg knew Welles sporadically and occasionally worked as his assistant, and had long been rumoured to be his son given their strong physical resemblance, he refused to believe such rumours until he eventually took a paternity test in 2010.[73] In her autobiography, In My Father’s Shadow, Feder wrote about being a childhood friend and neighbor of Lindsay-Hogg’s and always suspecting he might be her half-brother.[74]

After the death of Rebecca Welles Manning, a man named Marc McKerrow was revealed to be her biological son, and therefore the direct descendant of Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth. McKerrow’s reactions to the revelation and his meeting with Oja Kodar are documented in the 2008 film Prodigal Sons.[75] McKerrow died June 18, 2010.[76]

Despite an urban legend promoted by Welles himself, he was not related to Abraham Lincoln’s wartime Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles. The myth dates back to 1944 when, bantering with Lucille Ball on The Orson Welles Almanac before an audience of U.S. Navy service members, Welles says, “my great-granduncle was Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy in Lincoln’s cabinet”.[77] In a 1970 TV interview on The Dick Cavett Show, Welles refers to Gideon Welles as his great-grandfather. As presented by Charles Higham in a genealogical chart that introduces his 1985 biography of Welles, Orson Welles’s father was Richard Head Welles, son of Richard Jones Welles (born Wells), son of Henry Hill Wells (who had an uncle named Gideon Wells), son of William Hill Wells, son of Richard Wells (1734–1801).[9]

Welles is related to Charles Head (1899–1951), first husband of costume designer Edith Head (1897–1981). They are direct descendants of Henry Head (1647–1716), who emigrated to America before 1683 and settled in Little Compton, Rhode Island..

Physical characteristics

“Never robust, even as a baby Welles was given to ill health”, wrote biographer Frank Brady, who notes that from infancy he suffered from asthma, sinus headaches and back pain, with bouts of diphtheria, measles, whooping cough and malaria. “As he grew older,” Brady wrote, “his ill health was exacerbated by the late hours he was allowed to keep [and] an early penchant for alcohol and tobacco”.[1]:8

Welles reached a height of six feet at the age of 14.[9]:50 Peter Noble’s biography describes him as “a magnificent figure of a man, over six feet tall, handsome, with flashing eyes and a gloriously resonant speaking-voice”[78] According to a 1941 physical exam taken when he was 26, Welles was 6 feet (183 cm) tall and weighed 218 pounds (99 kg). His eyes were brown.[79] Other sources cite that he was 6 feet 4 inches (193 cm) tall, but the slates from costume tests made during the 1940s show him as 6 feet 1 inch (185 cm). Welles gained a significant amount of weight in his 40s, eventually rendering him morbidly obese, at one point weighing nearly 400 pounds (180 kg). The weight gain may have caused him to appear slightly shorter than his actual height. His obesity was severe to the point that it restricted his ability to travel, aggravated other health conditions, including his asthma, and even required him to go on a diet in order to play the famously portly character Sir John Falstaff.[80] Some have attributed his over-eating and drinking to depression over his marginalization by the Hollywood system.[81]

Religious beliefs

When Peter Bogdanovich once asked him about his religion, Orson Welles gruffly replied that it was none of his business. Welles then added that he was raised Catholic — “and once a Catholic, always a Catholic, they say.”[13]:xxx In an April 1982 interview, Merv Griffin asked Welles about his religious beliefs. Welles replied, “I try to be a Christian. I don’t pray really, because I don’t want to bore God.”[1]:576

Politics

Welles was politically active from the beginning of his career. He remained aligned with the left throughout his life, and always defined his political orientation as “progressive“. He was a strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, and often spoke out on radio in support of progressive politics. He campaigned heavily for Roosevelt in the 1944 election.

For several years, he wrote a newspaper column on political issues and considered running for the U.S. Senate in 1946, representing his home state of Wisconsin (a seat that was ultimately won by Joseph McCarthy).

In 1970, Welles narrated (but did not write) a satirical political record on the administration of President Richard Nixon titled The Begatting of the President.

He was also an early and outspoken critic of American racism and the practice of segregation.

Death and tributes